5th March, 2005

Two Mexican regional songs in a row in the #1 spot might suggest that 2005 is seeing something of a return to traditionalism; but although certainly there was and is overlap between the Conjunto Primavera's fanbase and Intocable's, they're also very, very different bands with different approaches to their material.

Part of that is just the difference between conjunto chihuahuense and a tejano ballad band; although they both feature prominent accordion, square rhythms, and romantic vocals, Primavera's Tony Melendez is a squarely traditional singer in an almost bel canto tradition, perfect at making itself heard in unamplified plazas, while Intocable's Ricardo Muñoz is, well, Texan: his vocal technique is derived from African-American soul and the longstanding intimacy of US pop recording.

And that's the real difference: between Mexican regional music and tejano, which is marketed as Mexican regional music (and is quite popular in many regions of Mexico), but is also part of the larger North American pop universe. Intocable (whose name means Untouchable; the Clint Eastwood movie was five years old when they first started using the name) is as much a U.S. band as a Latin one; they're just so wildly popular in the Latin market that they don't need recognition from the Anglophone portions of the U.S.

That "Aire" is our first encounter with them is due to chance more than to their popularity; they've been million-sellers since the late 90s, and it's not even necessarily one of their most popular songs. But it is a great song: straightforward and beautiful, with enough rhythmic shifting to remain interesting (the underwater half-time middle eight is a remarkable effect in a #1 song) and such a lovely, vulnerable central performance from Muñoz that even the rather hackneyed lyrics of the chorus ("tú eres aire que respiro," you are the air I breathe) sound invested with emotion and, thereby, truth.

Intocable's ability to invest traditional tejano instrumentation and structure with North American pop gloss and soul emotionalism have made them so wildly popular for forty years that it's a shame this is the only time we'll meet them on this travelogue, at least as of this writing. I wouldn't be at all surprised if they somehow gamed the streaming era too, though.

Showing posts with label tejano. Show all posts

Showing posts with label tejano. Show all posts

22.10.18

6.8.18

JENNIFER PEÑA, “VIVO Y MUERO EN TU PIEL”

29th May, 2004

If Jennifer Peña's career proceeded in emulation of Selena's, this might be the point where Selena's ended: with a frosty, devotional ballad. But Jennifer never crossed over to the English language, preferring to remain resolutely, and indeed polyphonically, Latin -- the regionally-aimed cumbia version of the song also had a video, in which her hips move with much greater freedom than they do in the canonical ballad version -- and this is her last appearance in our travelogue. She would only issue one more studio album, and then marriage (to Obie Bermúdez?!), her recording contract going into legal limbo as a result of label mergers, and finally a turn to Christian music would sideline her pop career for good.

The parent album, Seducción, also featured a salsa version of this song among its bonus tracks, because although the recording industry was undergoing the precipitous slide from its millennial peak, diversification was still a good bet. But it was the pop ballad version that was the hit, judging by its view count (although the cumbia version sounds much more lively and interesting at a remove of fourteen years), and Rudy Pérez's mooning lyrics about the overwhelming, totalizing way that the early stages of a crush affects the enamored one only really make sense in a ballad form: in the cumbia, such lugubriousness ring hollow among so much boot-scooting good cheer.

"Vivo y Muero en tu Piel" means "I live and die in your skin," a striking image that, in the context of the song, is really just an elaboration of the "whither thou goest, I will go" of Ruth 1:16. And I'm reminded again of how much more sensual, how much more willing to consider physical bodies and mention skin and flesh, Latin pop is than Anglo pop. The fundamental Gnosticism of American religion, its pretense that love can be purely an intellectual-emotional exercise without corresponding physicality, casts long shadows.

The parent album, Seducción, also featured a salsa version of this song among its bonus tracks, because although the recording industry was undergoing the precipitous slide from its millennial peak, diversification was still a good bet. But it was the pop ballad version that was the hit, judging by its view count (although the cumbia version sounds much more lively and interesting at a remove of fourteen years), and Rudy Pérez's mooning lyrics about the overwhelming, totalizing way that the early stages of a crush affects the enamored one only really make sense in a ballad form: in the cumbia, such lugubriousness ring hollow among so much boot-scooting good cheer.

"Vivo y Muero en tu Piel" means "I live and die in your skin," a striking image that, in the context of the song, is really just an elaboration of the "whither thou goest, I will go" of Ruth 1:16. And I'm reminded again of how much more sensual, how much more willing to consider physical bodies and mention skin and flesh, Latin pop is than Anglo pop. The fundamental Gnosticism of American religion, its pretense that love can be purely an intellectual-emotional exercise without corresponding physicality, casts long shadows.

Labels:

2004,

ballad,

cumbia,

jennifer pena,

r&b,

romantica,

rudy perez,

tejano,

usa

4.12.17

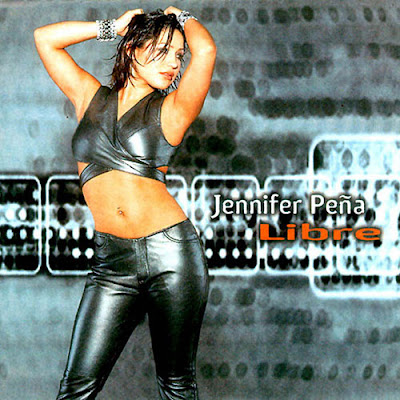

JENNIFER PEÑA, “EL DOLOR DE TU PRESENCIA”

24th August, 2002

The hunger, as much spiritual as commercial, for a replacement for Selena had been an undercurrent of the Latin music industry since her death. One of the likeliest candidates was Jennifer Peña, whose first large-stage performance had been at a Selena tribute concert at the Astrodome in 1995, when she sang "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" at eleven years old. She was already being managed by Selena's father; her debut album as a singer fronting Jennifer y los Jetz, would be released the following year.

But like Selena herself, her career was less one of meteoric success than of constant work, slow movement forward, and gradual leveling-up. Libre, released in 2002 when she was eighteen, was her fifth album, but the first attributed entirely to her name and also the first after jumping from EMI, where the Quintanillas had signed her, to Univision, which had also broken Selena widely in 1993. She retained the cumbia sound which was her signature, but with production from Rudy Pérez and Kike Santander, aimed more squarely at the broader Latin Pop market.

It worked, clearly. "El Dolor de Tu Presencia" (the pain of your presence) is both a lush r&b ballad and a skanking cumbia jam, with pure pop harmonies and a bassline that won't stop. Although it was written by Rudy Pérez, it's very much a teenager's song, moaning about how the boy she's in love with is in love with her best friend, tearing their friendship apart and causing her pain. Still, it's smartly produced and sung with a warmth older than her years.

A power-ballad pop version, all swelling strings and crashing drums, was also released, which no doubt had a lot to do with bringing it to #1 (cumbia remained popular on the border, but not necessarily in the larger US Latin Pop market), but the cumbia rendition made the video, which cuts shots of her mooning over the love triangle with shots of her dancing in front of her cumbia band, acknowledging that after all, everything's a performance.

But like Selena herself, her career was less one of meteoric success than of constant work, slow movement forward, and gradual leveling-up. Libre, released in 2002 when she was eighteen, was her fifth album, but the first attributed entirely to her name and also the first after jumping from EMI, where the Quintanillas had signed her, to Univision, which had also broken Selena widely in 1993. She retained the cumbia sound which was her signature, but with production from Rudy Pérez and Kike Santander, aimed more squarely at the broader Latin Pop market.

It worked, clearly. "El Dolor de Tu Presencia" (the pain of your presence) is both a lush r&b ballad and a skanking cumbia jam, with pure pop harmonies and a bassline that won't stop. Although it was written by Rudy Pérez, it's very much a teenager's song, moaning about how the boy she's in love with is in love with her best friend, tearing their friendship apart and causing her pain. Still, it's smartly produced and sung with a warmth older than her years.

A power-ballad pop version, all swelling strings and crashing drums, was also released, which no doubt had a lot to do with bringing it to #1 (cumbia remained popular on the border, but not necessarily in the larger US Latin Pop market), but the cumbia rendition made the video, which cuts shots of her mooning over the love triangle with shots of her dancing in front of her cumbia band, acknowledging that after all, everything's a performance.

Labels:

2002,

ballad,

cumbia,

jennifer pena,

kike santander,

pop idol,

r&b,

rudy perez,

tejano,

usa

10.2.11

MARCO ANTONIO SOLÍS, “QUE PENA ME DAS”

27th July, 1996

Marco Antonio Solís' triumphant return to the top spot as a solo act, having finally shaken off even the name of Los Bukis, is ironically (or perhaps not so ironically, given the trend of number-one songs in the mid-90s) much less pop and much more traditional Mexican regional, with a twelve-string bajo sexto as the lead instrument whenever Solís isn't singing, and a rhythmic bed that makes room for the lazy scrape of the Afro-Latin güiro and the urgent thunk of a cowbell in addition to the drumpad fills he's always been singing over.

The song itself is a plaintive lament — "Que Pena Me Das" translates literally as "What Trouble You Give Me" (though "pena" is a flexible term that can mean anything from lasting grief to momentary annoyance) — about a woman who has gone chasing after money and left her lover disconsolate. It's pretty, but extremely traditional, and Solís continues his march through the charts as the most successful inconsequential artist we've spent a good deal of this travelogue running into occasionally.

This song, in fact, marks the end of the first decade of the Hot Latin chart, as it remained at the top of the chart through much of September, the one-year anniversary of Rocío Dúrcal's "La Guirnalda," the song at the top when Billboard first published the chart. If we'd heard none of the intervening songs, it would be tempting to imagine that not much had changed in a decade, but much has and there's much more to come.

But I wanted to mark this anniversary by first, thanking everyone for reading so far with me (thanks! you're the best!), and then asking for feedback. What works about this blog? What doesn't? Should I post video? Would it be helpful, or maybe more conducive to triggering conversation, if I gave these songs a mark out of ten, as Tom does on Popular and Sally does on No Hard Chords? I'd love to hear what anyone besides me thinks about any of these songs in particular, or about the blog in general, whether you leave comments here, at my Tumblr, or via e-mail. Especially if you know more about the subject than I do — which isn't hard at all, I'm winging every one of these posts.

Regardless, it's been a lot of fun to trawl through the past ten years. But I make no secret that I'm really looking forward to the next fourteen and counting. Latin Pop, not unlike its Anglophone counterpart, has only gotten better as the millennium turns. How so? Keep reading.

1.2.11

OLGA TAÑÓN, “¡BASTA YA!”

18th May, 1996

Of course, no sooner is there a new normal — with regional Mexican and border styles suddenly making up a huge proportion of the top of the Latin chart, displacing the old school of blowsy ballads punctuated by sassy dance numbers — than the professionals and the pop lifers start moving in to take it over.

Of course, no sooner is there a new normal — with regional Mexican and border styles suddenly making up a huge proportion of the top of the Latin chart, displacing the old school of blowsy ballads punctuated by sassy dance numbers — than the professionals and the pop lifers start moving in to take it over.

Olga Tañon is a new name in these parts, but a minimum of research uncovers a very familiar name. Marco Antonio Solís, the long-haired, blandly sentimental leader of Los Bukis and latterly a solo artist, wrote and produced the album Nuevos Senderos in a transparent bid to fill the void which the death of young miss Quintanilla-Pérez had left in the affections of Latin Pop listeners all over the hemisphere. Tañon had been singing for years -- in fact her career pretty closely parallels that of Selena's, with Puerto Rico standing in for Tejas, and merengue for tejano.

Still, this is supposed to be a tejano song (you can hear, very faintly, a cumbia rhythm in the verses), and even though it was (briefly) successful, it's no replacement for Selena. Solís drowns everything in his signature bland soup of cascading keyboard riffs and too-patient drum fills, and Tañon's voice is neither as charged nor as flexible as Selena's; the overall effect is that of a script being dutifully followed. Which doesn't mean there aren't pleasures to be had in the song, just that they are minor and without the urgency that the lyrics provide — "¡Basta Ya!" means "Enough Already!", but both the chiming melody and Tañon's too-elegant phrasing give it the sound of a treacly lament instead of the desperate, long-awaited standing-up-for-herself that you get from a straightforward reading of the lyrics.

This isn't Olga Tañon's last appearance in our travelogue, but I'm hoping for something a little more lively in our next encounter.

Labels:

1996,

ballad,

marco antonio solis,

mexico,

olga tanon,

puerto rico,

regional,

tejano

23.12.10

SELENA, “FOTOS Y RECUERDOS”

On March 31st, after an argument with a former employee and president of her fan club, Selena turned to leave the Days Inn room where they had agreed to meet and was shot deep in the right shoulder. She died of blood loss just over an hour later in a Corpus Christi hospital.

The immense and immediate public grief that followed was the occasion of most Anglophone music fans' first hearing of her. Tom Brokaw called her "the Madonna of Mexico" on the evening news, but he was wrong. She was the Madonna of America — of that portion of America which, just as free and proud and God-fearing as any other, has worked harder, lived on less, and built more (at least west of the Mississippi). Mexico? Please. Selena was from Texas.

(Which isn't to say she wasn't proud of her Mexican heritage, same as anyone can be of their Irish or Italian or whatever. Just noting acts of erasure where I see them.)

And by now hopefully you'll have clicked play and wondered why I haven't yet mentioned the song. It's a great song even if you don't know Spanish, and you recognized that guitar line right away. But although it was her first number one after her death, it was the fourth single from Amor Prohibido, and so even if the imagery was kind of apt (see below), there was always going to be a feeling of exhaustion to whatever song took this place.

But the fact that it's a rewrite of perhaps the most buoyant, sparkling song of ache and loss ever written (even if Chrissy Hynde's new-wave Kinksisms have little in common with Selena's skanking cumbia) very nearly lifts it above mere fourth-single roteness and into something grander, more eloquent: a self-eulogy. The Spanish lyric, written by Ricky Vela, takes its lead from the opening line of the original — "I found a picture of you" — and sticks to the image. Selena sings "tengo fotos y recuerdos" ("I [only] have photos and memories") over the title melody, and while her background singers gamely imitate the "ooh ahh" chants which Hynde had borrowed from Sam Cooke, the chain-gang metaphor is lost in translation. Still, the rising "oh-oh-a-oh-ohhh" and the descending, patient guitar figures of the original remain, and in any language it's a beautiful song.

We will see Selena from this deck only once more; we barely got to know her, and already she's slipping out of sight. It would probably be too much to say she changed everything. But she changed enough; the rest of this travelogue will be that much better for all the ways she pushed Latin Pop forward.

20.12.10

LA MAFIA, “TOMA MI AMOR”

8th April, 1995

When the Hot Latin chart goes norteño, it goes norteño all the way. Forget the politesse of Bronco's string arrangement, or La Mafia's own concessions to electronic modernism — this is the raw stuff, accordion and rhythm section and a singer gritando puro campesino. It's a rare example of a live hit, always unusual outside of 70s AOR, and the fact that it was only on the top of the chart for a week detracts nothing from the fact that hey, it was at the top of the chart at all.

But it's not just the crowd noise that makes this the rawest, most rock & roll record we've encountered yet in our journey. The stiff polka-descended rhythms might not sound very raucous, but the accordion positively shreds, and the gritos aren't a million miles away from Joe Strummer's Peter Pan crows on "London Calling," or from cowboy whoops presaging heavy sales at the saloon and a gunfight in the morning. Sure, people who aren't used to norteño might mutter "Chicken Dance" to themselves, and the lyrics are very nearly simple enough to be a playground chant, but there's a magnificent energy to the song, an organic looseness that suggests that maybe more Latin Pop should have been released to radio from concert recordings.

"Toma Mi Amor" means "take my love," but the verb "tomar" ("take") is also used to mean "drink" — and La Mafia doesn't hesitate to let the suggestiveness bubble up to the surface. It's a bar-band singalong from South Texas, where bar bands are just as likely to be brown as white, and their crowds are composed of shitkickers, hard-working alcoholics, and horndogs either way.

13.12.10

LA MAFIA, “ME DUELE ESTAR SOLO”

21st January, 1995

La Mafia's previous appearances in these pages have been piano ballads, tasteful — of their kind — and even excessively polite, as though they had put on their good suits in order to enter the charts and were reluctant to turn around for fear something might break. But something happened between then and now; even though their previous single was off the same album, it's highly unlikely this one would have made it to the top if it weren't for the gravitational force exerted by the high-mass formation of a new star.

La Mafia's previous appearances in these pages have been piano ballads, tasteful — of their kind — and even excessively polite, as though they had put on their good suits in order to enter the charts and were reluctant to turn around for fear something might break. But something happened between then and now; even though their previous single was off the same album, it's highly unlikely this one would have made it to the top if it weren't for the gravitational force exerted by the high-mass formation of a new star.

Tejano, the specifically Texan homebrew of cumbia, norteño, and American r&b and pop, was the new sound of Latin radio, and the way La Mafia presses hard on cumbia's Caribbean beat, skanking hard at reggae tempos, may be the funkiest sound we've had to date. As well as one of the tackiest — speaking as someone who grew up in the late 80s and early 90s, there are class and taste implications in the cheap keyboard sounds and drum-machine presets La Mafia use here that still trigger hot floods of embarrassment deep in my subconscious. But I'm learning to own it, to even rejoice in it (the unlikely reappearance of similar off-brand synth textures on the radio in 2011 is some help here), and the groove bounces enough to forgive anything.

Or maybe I'm just overidentifying with the lyrics. "Me Duele Estar Solo" means "it hurts to be alone," and the fact that the self-pitying lyrics are sung with such a smooth, carefree delivery over a very sunny bounce only appeals even more to someone who prefers to wrap unflattering self-pity in a breezy irony that dares anyone else to feel sorry for me. (I didn't say I succeed.) If it's a little hard to imagine raising a maudlin glass to the chorus, that's only because bopping to the rhythm might spill the beer.

9.12.10

SELENA, “NO ME QUEDA MÁS”

17th December, 1994

We close out 1994 appropriately, with the woman who owned 1994 top-to-bottom. It's her fourth number one of the year, and on first listen it's her least modern. It sounds like it could have been recorded in the sixties or even earlier, all tight-strummed guitars and a mini-orchestra pumping film-cue trills in on every bar. The lush r&b of "Dondequiera Que Estés," the skanking cumbia of "Amor Prohibido" and "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" are nowhere to be found here; Ana Gabriel, or even Rocío Dúrcal, could just as easily have recorded this.

We close out 1994 appropriately, with the woman who owned 1994 top-to-bottom. It's her fourth number one of the year, and on first listen it's her least modern. It sounds like it could have been recorded in the sixties or even earlier, all tight-strummed guitars and a mini-orchestra pumping film-cue trills in on every bar. The lush r&b of "Dondequiera Que Estés," the skanking cumbia of "Amor Prohibido" and "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" are nowhere to be found here; Ana Gabriel, or even Rocío Dúrcal, could just as easily have recorded this.

Which is partly the point. Latin music is just as much invested in understanding itself as existing in continuity with grand old traditions as country music is; understandably so, given the socially conservative makeup of both core audiences. Selena is very much a way into the future, but she knows that her novelty exists on sufferance: without explicit nods, explicit ties to the past, she remains on unstable ground, as easily dropped as any other novelty. And of course she loves the grand old traditions herself; listen to how enthusiastically she rips into the traditional sobbing ranchera style of singing. Juicy melodramatics no know expiration date.

But the song only sounds old; it was written by Ricky Vela, who was in love with Selena's sister Suzette, after she married, and it's not in the old florid poetic style of traditional bolero ranchero. The vivid images of traditional romántico are left behind as the lyrics deal only in direct emotions; this is a song about how loss of love shatters a person's conception of self, and Vela baldly states it. The opening lines, "no me queda más/que perderme en un abismo de tristeza y lágrimas" translate to "I have nothing left/but to lose myself in an abyss of sadness and tears." It's mopey stuff, for sure; but Selena's vibrant performance, and the refusal of the music to get maudlin, rescues it. Which isn't to say that the song isn't better-written than Selena's previous number ones (not that great writing is everything) — Vela's Spanish is much less basic than A. B. Quintanilla's.

Selena has conquered her world. Dance, ballads, funk, traditional music; she can do it all. Naturally, her sights are set higher still; there's a whole other market out there still to conquer. 1995, and all it will bring, waits right around the corner. No spoilers.

29.11.10

SELENA, “BIDI BIDI BOM BOM”

22nd October, 1994

Tom Ewing’s Popular column at Freaky Trigger — on which this blog is unashamedly based — has a graphic at the top which changes out every so often, using a picture of the biggest pop star(s) of the era that Tom’s covering to orient the readership in the historical moment. If this blog had a similar graphic, Selena would be the unquestioned icon of this age. Not only was she the biggest Latin Pop star of her era — big deal, lots of people have been for lots of respective eras — but she was one of the biggest stars of her era period, doing for Latin Pop roughly what Taylor Swift (at the moment of writing) has been doing for country-pop. Namely, revitalizing it for a lot of people and confirming a lot of other people’s biases against it; a pop star’s probably not doing her job if a significant amount of people don’t hate her.

The title phrase “bidi bidi bom bom” isn’t dictionary Spanish, but onomatopoeia for the giddy beating of a heart. (A rough translation might be “thumpa thumpa dum dum.”) The lyrics, insofar as they matter beyond the gorgeous swell of Selena’s ex tempora vocalizing, are all about how her heart races when someone walks by or speaks in her hearing. The verses are so magnificently generalized, so completely abandoned to anyone’s use, that not even a gender is attributed to the person who’s to blame for this arrhythmia, just a third-person tense. It’s an intentionally slight song, and Selena delivers a complementary performance. You couldn't describe it as slight, not with that lungpower, but it has the impermanence of real joy — even as you try to latch onto it, it flutters away.

Tom Ewing’s Popular column at Freaky Trigger — on which this blog is unashamedly based — has a graphic at the top which changes out every so often, using a picture of the biggest pop star(s) of the era that Tom’s covering to orient the readership in the historical moment. If this blog had a similar graphic, Selena would be the unquestioned icon of this age. Not only was she the biggest Latin Pop star of her era — big deal, lots of people have been for lots of respective eras — but she was one of the biggest stars of her era period, doing for Latin Pop roughly what Taylor Swift (at the moment of writing) has been doing for country-pop. Namely, revitalizing it for a lot of people and confirming a lot of other people’s biases against it; a pop star’s probably not doing her job if a significant amount of people don’t hate her.

If “Amor Prohibido” was her all-conquering single, the first triumph in her own voice and style which made her queen over a vast territory of pop, “Bidi Bidi Bom Bom” represents a consolidation of power — she’s not just a lament-singer, she can do uptempo dance music too. Not too uptempo — the cumbia rhythm and skanking guitars suggest a lazy beachfront jam rather than a hot dancefloor stomp — but funky and playful where she’s previously been anthemic, even melodramatic. The secret theme of Nineties Music, cross-genre mélange, is given superb form here: Selena combines cumbia tejano, coastal reggae, beach funk, florid r&b vocalizing, and a crisply, bluesy guitar solo into a perfectly-balanced solution that contemporary “eclectic” magpies like Beck or that dude from Soul Coughing might envy.

The title phrase “bidi bidi bom bom” isn’t dictionary Spanish, but onomatopoeia for the giddy beating of a heart. (A rough translation might be “thumpa thumpa dum dum.”) The lyrics, insofar as they matter beyond the gorgeous swell of Selena’s ex tempora vocalizing, are all about how her heart races when someone walks by or speaks in her hearing. The verses are so magnificently generalized, so completely abandoned to anyone’s use, that not even a gender is attributed to the person who’s to blame for this arrhythmia, just a third-person tense. It’s an intentionally slight song, and Selena delivers a complementary performance. You couldn't describe it as slight, not with that lungpower, but it has the impermanence of real joy — even as you try to latch onto it, it flutters away.

11.11.10

SELENA, “AMOR PROHIBIDO”

11th June, 1994

There are at least five takes on this song battling each other to get out of me, so let's see how well I can juggle.

First let's talk about Selena. We already have, a bit, but those were only voices crying in the wilderness make straight the paths. Here she is herself, incarnate, not mediated by other voices, other scripts, other genres. (Of course, since she wasn't actually divine — more's the pity — this too is mediated, particularly by her producer and older brother A. B. Quintanilla III and frequent colaborator Pete Astudillo. But more about that below.) But this is not only Selena having greatness thrust upon her, this is the achievement of greatness by a woman who has worked very hard for many years and has made a breakthrough that is as much artistic, personal and cultural as it is commercial. She's sung rings around the Barrio Boyzz already, but that was as though to prove she could, matching a genre and a sense of place that isn't hers. Because although at age twenty-three she has lived anywhere in the Spanish-speaking US that she could perform, from quinceañeras and state fairs to nightclubs and dancehalls to video shoots and awards banquets, she is a Texas girl at heart, with all the many meanings that phrase can have.

There were Texans long before there was a Texas, and she has roots that go back farther than Sam Houston or even Cabeza de Vaca. Her beauty is not just the high-contrast drama of the chola (though there's that too), but the imperious impassivity of the indigena, and she has always been royalty. And the music she makes is Texan: planted square on the ground, grounded in traditional identities even as it races forward into technofuturism, and bigger and better than anything else around. The word is tejano, which means Texan and was there first, and the rhythm is cumbia, and it's been the rhythm of poor latinoamericanos since at least the 1950s, when it first spread from the coasts of Colombia, where it was invented by Africans, Europeans, and Indians working together even though only one of the races was not bought and sold and killed like property.

And this is where it gets personal, because I, who am not descended from slaves whether African or American, first heard the cumbia rhythm as the celebratory music of poor Latin Americans when I lived in Guatemala, not a boy but not yet a man, and I took against it from the first. I am ashamed to write these words, ashamed of the repulsion my virgin white mind felt — still feels on occasion, when I don't trample it down and snarl through gritted teeth to listen, dammit — because I experienced poverty in those days as an Other, a brown and crippled and foul-smelling horror which I would do anything to get away from. With its stiff, poky gait, cumbia became a visceral representation of my colonial disgust with native life and culture. This is me calling myself racist. And this is me reminding myself that the previous sentence doesn't get me, or anyone, off the hook.

It wasn't until investigating Argentinean music earlier this year (for entirely unrelated reasons) that I learned to hear cumbia as the tropical rhythm it is — not a million miles from one-drop reggae, in fact — instead of as the undifferentiated, droning, dull party music of poor Mayans in the Sierra Madre highlands I originally took it for. And even then, it took a modern indie-pop version before the penny dropped.

The Texan version of cumbia, which has been running strong since the 1970s, owes a little more to Mexican norteña and American country, and it might help unfamiliar ears to think of Selena as the Mexican-American equivalent of Faith Hill or Shania Twain, riding a retrofurbished boot-scootin' boogie to gleaming modernist pop ends. And the cumbia rhythm makes "Amor Prohibido" that rare encounter in this travelogue, a midtempo song, neither baile nor balada, but pop, with a funky drive to the beat that makes it nearly impossible not to sway along even if it's not fast enough for athletic dancing. Traditional cumbia dance, with its short, intricate steps, does in fact require boots to scoot; it was originally a working-class courtship ritual.

Finally (and speaking of ritual!), the lyric deserves examination. The title translates as "Forbidden Love," and if the phrase doesn't have quite the same charge in Spanish as it does in English, where connotations of closeted homosexuality have accreted over the years, it's still a rich pop vein to mine. Selena, perhaps appropriately for her big, splashy introduction to the wider Latin Pop world, takes a Romeo And Juliet tack. The chorus runs:

Amor prohibido, murmuran por los calles

Porque somos de distintas sociedades

Amor prohibido, nos dice todo el mundo

El dinero no importa en tí y en mí

Ni en el corazón

Oh oh, baby

Which, before I provide the translation, I should point out is the Spanish of someone for whom Spanish is not their first language: this is a very basic lyric in both vocabulary and ideas, and perhaps all the more successful for it. (Not everyone who listens to Latin Pop in the US is as comfortable with Spanish as their parents or grandparents were. And not everyone who speaks Spanish is educated in it.) Translated, it runs:

Forbidden love, they whisper in the streets

Because we are from different societies

Forbidden love, says the whole world to us

Money doesn't matter to you or to me

Or to the heart

Oh oh, baby

This entire travelogue has taken place in the shadow of another, much larger pop scene just beyond the borders of this one. We have encountered it here and there — Los Lobos, Jon Secada, and Gloria Estefan all crossed the border regularly — but for the most part Latin Pop has been a shadowy, underrepresented underclass, and the Anglophone Pop which sits by it on the radio is bigger, louder, more violent, and in its wholesale domination of the discourse, as colonial and even oppressive as anyone who wanted to make the two pop scenes a metaphor for the two (for which read multiple) societies could wish.

If I used blasphemously Christological language about Selena earlier, it's precisely because she was uniquely positioned, for a brief period, to bridge that gap. For many people, in fact, she did; and one reason that I've spent so much (so much!) time talking about her is that she's still one of the Names that even people who don't know anything about Latin Pop know. We'll have plenty more opportunities to talk about what exactly was lost; "Amor Prohibido" by no means sums up her contribution to Latin Pop — fuck that, to Pop, punto y final. But it's a fantastic best foot forward, a progressive anthem of racial and cultural (and sexual, if you want it to be) unity taking its cues from traditional sounds that might even play as hokey to some ears. She would fly yet higher; but I'm not sure that she ever burned brighter.

4.11.10

LA MAFIA, “VIDA”

7th May, 1994

A rising tide lifts all boats. The last time we heard from La Mafia, the Texan romántica group, they were still in an 80s hangover, with thin production and warbly synths that didn't even rise to the gloss of Los Bukis. But the game's been raised: Jon Secada and Gloria Estefan are making pop as burnished and high-definition as anyone anywhere, and there's less excuse for Latin Pop to languish in a ghetto of underproduction and out-of-date sounds just because its audience is poorer (on average) than the wider pop audience. It's the 90s — everyone's getting richer.

A rising tide lifts all boats. The last time we heard from La Mafia, the Texan romántica group, they were still in an 80s hangover, with thin production and warbly synths that didn't even rise to the gloss of Los Bukis. But the game's been raised: Jon Secada and Gloria Estefan are making pop as burnished and high-definition as anyone anywhere, and there's less excuse for Latin Pop to languish in a ghetto of underproduction and out-of-date sounds just because its audience is poorer (on average) than the wider pop audience. It's the 90s — everyone's getting richer.

As a song, this isn't much: the central conceit, that he's singing to Life itself as if it were a woman (or to a woman as though she were Life itself; it's pleasantly ambiguous), is a standard of romantic poetry, and everyone from Shakespeare to Tumblr kids have had a run at it. Melodically, it's a little restrictive, plodding along in the same key without much variation, and Oscar De La Rosa, the vocalist, could either be commended for his restraint or (more likely) just called boring; the very brief moment towards the end when he goes off-script and starts singing with a bit of soul is what a lifetime of Anglophone pop listening was leading me to expect at every moment.

But it's the the production, classy without being stiff or standoffish, that makes the song for me. I love the sound of a piano — real piano, not synthesized approximations — and its appearance as the lead instrument here disposed me favorably towards the song anyway. Then the gorgeous Spanish guitar solo shows up, and I'm hooked. Even the backing strings are used tastefully, decorative rather than overwhelming, with a real sense of narrative flow which the song and the singer lack. If we must have ballads, I much prefer this style — intimate, tasteful, even restrained — to the emotionally extravagant bombast, whether orchestral or synthesized, which has so far been usual here.

1.11.10

BARRIO BOYZZ & SELENA, "DONDEQUIERA QUE ESTÉS"

We've encountered Selena before, but while she was notable, the song wasn't: a perfunctory saunter through a traditional romántico duet that almost anyone we've seen in these pages to date could have done just as well, to just as little effect. And she's back duetting with another flash-in-the-pan; for the second time, she's just about the only reason to pay attention to her partners' second (of two) appearances at the top.

But Barrio Boyzz, while they may not graze our notice again, have this much over Álvaro Torres: they sound like Now. The snapping new jack swing beat, the house piano, and the alternately lush and silky harmonies are all precisely where urban candyfloss pop was at in 1994, and Selena has outgrown her Ana Gabriel imitation, instead channeling an r&b diva that not only keeps up with but far outpaces the Boyzz. Their name was on the hit — she was officially a guest on their album, which was named for the song — but nobody buys Barrio Boyzz compilations for the song: by all reckonings, it's her first major hit, the place where Srta. Quintanilla-Pérez, quinceañera performer, talent-show winner, and jobbing local-circuit singer, became Selena, global pop star.

The song (as opposed to the production) is still not quite worthy of her talents. The translated title would be "Wherever You Are," and the chorus continues, just as tritely in Spanish as it comes out in English: "remember, I will be there at your side ... I think of you and feel for you ... I will always be your first love." But she has a sharper sense of rhythm than her duet partners and is in full command of her impressive vocal faculties, and once the dovey lyrics die down and she can just play with the beat, she scats circles around all of them. Not even Mariah was showboating like this; Mary J. Blige is about the only English-language equivalent, and she hadn't yet come fully into her own either.

But enjoy the breezy New York funk while it lasts; when she returns, it will be as a full-throated Texan, and the world will be, ever so briefly, hers.

13.9.10

LA MAFIA, “ME ESTOY ENAMORANDO”

10th April, 1993

Not since Los Lobos have we seen this particular configuration in this particular spot: La Mafia are, rarely for the #1 Hot Latin spot, a band; and even more rarely, they're U.S. citizens. Texans, born and raised, from the city of Houston, and if they sing in Spanish and play a particularly safe and sanitized version of the plaintive border pop music called tejano, that's perhaps less because they're aiming for global Latin pop dominance and more because regional pop in the 90s tended towards the safe and sanitized. This was the decade that begat alt-country, however unnecessarily; while adherents could hear the pain and glory in John Michael Montgomery, others heard only the slow, waxy merging of all romantic pop into one homogenous ball of keyboard-heavy gloop.

Tejano will also have its crowd-pleasing alternative forms in the years ahead; but for now, this spare, almost minimalist rendition of a soulful countryish melody, with its hushed vocals and bluegrassy harmonies on the chorus, is a great low-key introduction to one version of the genre. The song is a ballad, and a soppily conventional one at that ("me estoy enamorando" just means "I'm falling in love," and the rest of the lyrics don't get much deeper), but the stark backing and crisp drums add unexpected heft to the naked melody until it sounds almost profound, like a folk or gospel song without the specificity of either.

2.8.10

ÁLVARO TORRES & SELENA, “BUENOS AMIGOS”

6th June, 1992

As I keep saying, I'm learning to hear this stuff as I go along, which means that most of my writeups are more and more inadequate the further away from them I get. I'm bound to miss small, subtle social and cultural cues; but there are big obvious ones that drift past me unnoticed as well. The obvious word missing from the blocks of text when we last had Álvaro Torres before the board (only three hits ago, for crying out loud) was tejano.

As I keep saying, I'm learning to hear this stuff as I go along, which means that most of my writeups are more and more inadequate the further away from them I get. I'm bound to miss small, subtle social and cultural cues; but there are big obvious ones that drift past me unnoticed as well. The obvious word missing from the blocks of text when we last had Álvaro Torres before the board (only three hits ago, for crying out loud) was tejano.

Torres was born in El Salvador, and began his career in Guatemala, but by the time he was reaching the top of the Hot Latin charts he was based in the US, participating in Southern Florida's omnivorous Latin Pop machine. He'd had some success duetting with Mexican pop stars like Marisela and Tatiana, so while recording the album that would become his biggest-selling hit, he was paired with another young up-and-coming girl singer out of Texas, who had been doing the local pop circuit since she was thirteen, and was poised to be a breakout star in the Latin Pop community. How big a star, of course, and how quickly snuffed out, no one as yet had any idea.

She sounds, on this first encounter with the uppermost reaches of this chart — her home chart, as it were, the pinnacle of which she will claim a half-dozen more times before all is done — like a young woman who very much wants to be Ana Gabriel. Like Gabriel, she sounds instinctively at home with the woozy ranchera rhythm, with the triumphantly goofy (or goofily triumphant) synth-horn fanfare that introduces and punctuates the duet, with expressing emotion while holding back a steely unreachable self (shades also of Luis Miguel). And like Ana Gabriel, she comfortably and without showboating blows her duet partner out of the water. This is to be Álvaro Torres' last appearance in our travelogue; it's perhaps not his fault that he's so unmemorable in it.

Labels:

1992,

alvaro torres,

ballad,

duet,

el salvador,

selena,

tejano,

usa

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)