18th August, 2012

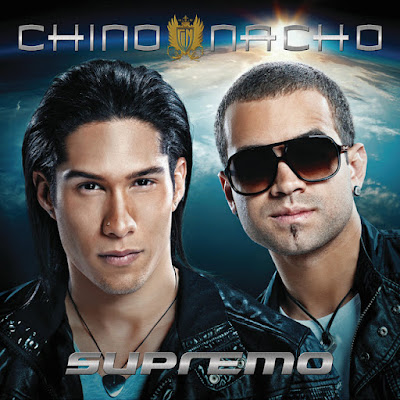

I genuinely adored Chino y Nacho's "Mi Niña Bonita", both at the time and in retrospect when I wrote about it here; but although this entry gets them out of being one-hit wonders, it has similar faults to many other attempted follow-ups to one-hit wonders: a lyric that reminds listeners of the previous song, a big-name (or as big as the budget allows) guest, an attempt to revamp a sound to keep up with musical fads. They've stripped out the reggaetón riddim, replacing it with a generic dance rhythm, invited British-Punjabi pop idol Jay Sean to croon some generic English-language sentiments, and infantilized the object of their affection even further, from niña bonita (pretty girl) to bebé bonia (pretty baby).

The result is a tune that slips off the mind as soon as it's been heard. Listeners seemed to agree; unlike the previous entry, which stuck around for three weeks, it's another of 2012's string of one-week #1s. Name recognition, quite possibly, was the only reason it charted this high in the first place, and the name that seems to bear the most weight is Jay Sean's: the musical bed powerfully recalls his three-year-old international smash "Down" -- which itself had been boosted by Lil Wayne's guest spot in a pop moment when Weezy F. Baby could do no wrong.

But perhaps the most contributing factor to the rote anonymity of the song is that great Dominican producer Richy Peña, who gave "Mi Niña" its charming gloss, has been traded out for Reggi El Auténtico, a Venezuelan newcomer just starting out on a vaguely notable career of producing and contributing songwriting for a host of Latin artists.

There's nothing actively wrong with "Bebé Bonita," and it fulfills its functions as a pleasant way to soundtrack dancefloor flirtation, as an eminently licensable piece of agreeable music for a youth-oriented advertising campaign, and as a career extender for the above-the-title names. They won't trouble us again; although Chino y Nacho have continued to have a hitmaking career, airwave-dominating success has been largely confined to Venezuela. But we'll always have "Mi Niña Bonita."