I try very hard to give every song that ever reached #1 on the Billboard Hot Latin chart a fair hearing. For most of its existence, I was not listening closely to Latin music, and so I come to most of it new; learning to listen past my immediate preconceptions and to consider each song within its immediate cultural, musical, national, and historical context, in addition to any it may have accumulated later, has meant ignoring the inevitable personal associations which any adult will have formed with various musical styles or production qualities. But I've met my breaking point.

The 1993 Bryan Adams/Sting/Rod Stewart hit "All for Love," from the soundtrack to a godawful Three Musketeers movie, has been my least favorite song of all time for the past three decades, for reasons that have almost nothing whatever to do with the song itself (although my critical assessment is that a schlocky piece of crap bellowed gracelessly by three aging buffoons), but rest entirely on my own personal emotional history. (Without going into details I once, in febrile adolescence, meant every word of it, which is reason enough to despise both it and myself till the end of time.) And so this gets caught in the conflagration.

Fonsi, Syntek, Schajris and Bisbal are no Adams/Sting/Stewart: they're still relatively young, for one thing, and their prettily-orchestrated power ballad doesn't have all the air sucked out of it à la Mutt Lang's signature production style in 1993. They also have prettier, stronger voices less overwhelmed by rock-god personality, and so they sound just as good harmonizing as on lead. But when I've said that, I've run out of compliments. Famous men trading off bellowed lines of a self-indulgent, self-regarding love song is my least favorite genre of music, and no amount of careful listening, sympathetic immersion in the individual histories of these four gentlemen, or imagining myself in the place of a listener to whom this song might once have meant the world, can budge me.

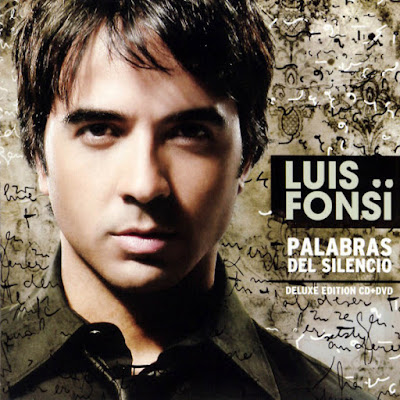

This is Puerto Rican Fonsi's sixth appearance here, a victory lap after "No Me Doy Por Vencido." He wrote the song for four male voices, and considered giving it to a boy band before asking his celebrity friends to record it during a fishing trip. Spaniard Bisbal has been here before, as has Argentine Noel Schajris, as one of the two masterminds of Sin Bandera; but this is Mexican pop-industry mainstay and commercial composer Syntek's debut. He, like everyone else here, displays no personality beyond being game and rather full of himself. The capacity of the Hot Latin chart in 2009 to absorb a wide variety of music from all over the Spanish-speaking world is still admirable; the fact that a song like this could get nowhere near #1 a decade later is, as a matter of cultural pluralism, a shame. But selfishly, I don't mind a bit.