29th July, 2006

Another minor first: the first reggaetón song to replace a reggaetón song at the top of the chart. Industry observers were quick to note all the signposts of a craze, which sounds comic from the vantage point of 2019, but it was not obvious at the time (especially if you were older than thirty and not attuned to Caribbean culture) that reggaetón would transform the pop landscape rather than burning bright before fading away like, say, Selena-era tejano.

But what Rakim (who would soon start spelling his name R.K.M. to avoid tripping over the legendary Long Island MC's trademark) and Ken-Y have introduced to reggaetón's quickly-growing multiplicity at the top of the chart is a pop element. We've seen pop reggaetón before, of course: but where Shakira and Alejandro Sanz were international pop stars borrowing the dembow riddim for some dancehall authenticity, Rakim and Ken-Y were a Puerto Rican reggaetón duo who aimed for uncomplicated pop sheen from the beginning, an unthreatening hearththrob version of Wisin and Yandel. (Four months ago, I contrasted Wisin & Yandel against Andy & Lucas; Rakim & Ken-Y split the difference.)

Rakim raps rather anonymously, Ken-Y croons in a falsetto-free Timberlake imitation, and they shift between Spanish and English so fluidly that it's hard to believe crossover appeal wasn't uppermost in their mind. The production by Mambo Kingz is similarly straightforward and frictionless, and the lyrics are so uncomplicatedly plaintive a recitation of romantic heartbreak (and so entirely free from the sexuality and violence which the moral guardians of Puerto Rican culture used to justify anti-reggaetón legislation) that these two perhaps better merit the comparison (which I levied against Shakira and Sanz) to the role Pat Boone played in rock 'n' roll history.

Which isn't entirely as a villain, but also as a prophet, hailing the domestication, prettification, and (yes) whitening of a once-dangerous music. For Rakim & Ken-Y, although they'll not trouble us again, set a template which pop-reggaetón crossover acts continue to follow to the present day. Late-2010s reggaetón, with its universalizing romanticism, sounds much less like mid-2000s Daddy Yankee, Don Omar, or Wisin & Yandel and much more like Rakim & Ken-Y. For what that's worth.

Showing posts with label pop idol. Show all posts

Showing posts with label pop idol. Show all posts

18.3.19

23.4.18

CHAYANNE, “UN SIGLO SIN TÍ”

6th September, 2003

Mere weeks after I complimented Ricky Martin for not letting himself be defined by songwriter Franco De Vita's lugubrious chest-beating sentiment-rock, I find that Chayanne has done exactly that. It's probably the best song, and almost certainly the best performance, that we've heard from him throughout this travelogue, but although he's well-suited to De Vita's sturdy, gospel-based sweeping chords and lead-footed rhythms, the result is a kind of emotionally-extravagant narcissist-rock that you have to be keyed into the emotions of or it will fall dispiritingly flat.

"Un Siglo Sin Tí" means "a century without you," and the lyrics of the song are a description of the singer's desolation at having been left, his contrition at having behaved badly, and his insistence that he has changed. Put that way, it doesn't necessarily sound very appealing (every abuser ever could sing along), but I've made the mistake before of believing that pop songs expressing sentiments that would be questionable in actual interpersonal relations are therefore worthless, and (especially) should not appeal to the female audience which does, in fact, enjoy them. Which is just an aesthetic extension on my part of Nice Guy syndrome. Nobody needs my thesis on why Chayanne's grand gesture at the end of the video is creepy.

Pop is, among much else, an idealized version of reality, a safe space where all emotions are allowed to play out without the repercussions that would attend them in life. Even in the real world closing out the possibility of actual contrition and actual forgiveness can be a mistake; but even if there are no good men in fact, let there be some in fiction.

"Un Siglo Sin Tí" means "a century without you," and the lyrics of the song are a description of the singer's desolation at having been left, his contrition at having behaved badly, and his insistence that he has changed. Put that way, it doesn't necessarily sound very appealing (every abuser ever could sing along), but I've made the mistake before of believing that pop songs expressing sentiments that would be questionable in actual interpersonal relations are therefore worthless, and (especially) should not appeal to the female audience which does, in fact, enjoy them. Which is just an aesthetic extension on my part of Nice Guy syndrome. Nobody needs my thesis on why Chayanne's grand gesture at the end of the video is creepy.

Pop is, among much else, an idealized version of reality, a safe space where all emotions are allowed to play out without the repercussions that would attend them in life. Even in the real world closing out the possibility of actual contrition and actual forgiveness can be a mistake; but even if there are no good men in fact, let there be some in fiction.

Labels:

2003,

chayanne,

franco de vita,

pop idol,

power ballad,

puerto rico,

rock en espanol,

romantica

4.12.17

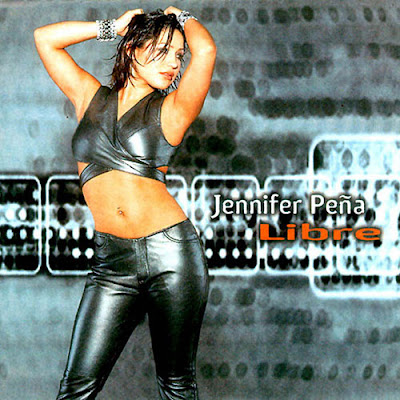

JENNIFER PEÑA, “EL DOLOR DE TU PRESENCIA”

24th August, 2002

The hunger, as much spiritual as commercial, for a replacement for Selena had been an undercurrent of the Latin music industry since her death. One of the likeliest candidates was Jennifer Peña, whose first large-stage performance had been at a Selena tribute concert at the Astrodome in 1995, when she sang "Bidi Bidi Bom Bom" at eleven years old. She was already being managed by Selena's father; her debut album as a singer fronting Jennifer y los Jetz, would be released the following year.

But like Selena herself, her career was less one of meteoric success than of constant work, slow movement forward, and gradual leveling-up. Libre, released in 2002 when she was eighteen, was her fifth album, but the first attributed entirely to her name and also the first after jumping from EMI, where the Quintanillas had signed her, to Univision, which had also broken Selena widely in 1993. She retained the cumbia sound which was her signature, but with production from Rudy Pérez and Kike Santander, aimed more squarely at the broader Latin Pop market.

It worked, clearly. "El Dolor de Tu Presencia" (the pain of your presence) is both a lush r&b ballad and a skanking cumbia jam, with pure pop harmonies and a bassline that won't stop. Although it was written by Rudy Pérez, it's very much a teenager's song, moaning about how the boy she's in love with is in love with her best friend, tearing their friendship apart and causing her pain. Still, it's smartly produced and sung with a warmth older than her years.

A power-ballad pop version, all swelling strings and crashing drums, was also released, which no doubt had a lot to do with bringing it to #1 (cumbia remained popular on the border, but not necessarily in the larger US Latin Pop market), but the cumbia rendition made the video, which cuts shots of her mooning over the love triangle with shots of her dancing in front of her cumbia band, acknowledging that after all, everything's a performance.

But like Selena herself, her career was less one of meteoric success than of constant work, slow movement forward, and gradual leveling-up. Libre, released in 2002 when she was eighteen, was her fifth album, but the first attributed entirely to her name and also the first after jumping from EMI, where the Quintanillas had signed her, to Univision, which had also broken Selena widely in 1993. She retained the cumbia sound which was her signature, but with production from Rudy Pérez and Kike Santander, aimed more squarely at the broader Latin Pop market.

It worked, clearly. "El Dolor de Tu Presencia" (the pain of your presence) is both a lush r&b ballad and a skanking cumbia jam, with pure pop harmonies and a bassline that won't stop. Although it was written by Rudy Pérez, it's very much a teenager's song, moaning about how the boy she's in love with is in love with her best friend, tearing their friendship apart and causing her pain. Still, it's smartly produced and sung with a warmth older than her years.

A power-ballad pop version, all swelling strings and crashing drums, was also released, which no doubt had a lot to do with bringing it to #1 (cumbia remained popular on the border, but not necessarily in the larger US Latin Pop market), but the cumbia rendition made the video, which cuts shots of her mooning over the love triangle with shots of her dancing in front of her cumbia band, acknowledging that after all, everything's a performance.

Labels:

2002,

ballad,

cumbia,

jennifer pena,

kike santander,

pop idol,

r&b,

rudy perez,

tejano,

usa

3.7.17

CHAYANNE, “YO TE AMO”

2nd December, 2000

Chayanne has mostly been an unremarkable, if consistent, presence in these pages: this is his fifth appearance since 1989, and there's not really been any narrative throughline to the songs with which he has bobbed to the surface. Blandly glamorous, suavely sentimental, with a thin, high voice which rarely changes even as the production drifts from moment to moment. The title of this new #1 is the kind of thing which needs to be a hell of a song to live up to its unadorned directness: how many really great songs called "I Love You" can there be?

This isn't one of them. It's fine: the lyric even acknowledges how hard it is to make "yo te amo" sound new, and the rhythmic descant on the chorus is a nice touch. The spacy 70s synthesizer which warbles up and down the track is the most interesting thing about the production, once more handled by Colombian mastermind Estéfano. The shuffling gospel rhythm already sounds dated; and while a full choir never comes in, there's enough claustrophobic thickness to the production that it's unnecessary.

Estéfano's lyric is really good, actually, worth looking up and reading through, whether in the original or translation. It's a more or less ordinary love song, but in its details and structure it's the kind of pop-literary performance that deserves a better song, and a better singer.

Chayanne has mostly been an unremarkable, if consistent, presence in these pages: this is his fifth appearance since 1989, and there's not really been any narrative throughline to the songs with which he has bobbed to the surface. Blandly glamorous, suavely sentimental, with a thin, high voice which rarely changes even as the production drifts from moment to moment. The title of this new #1 is the kind of thing which needs to be a hell of a song to live up to its unadorned directness: how many really great songs called "I Love You" can there be?

This isn't one of them. It's fine: the lyric even acknowledges how hard it is to make "yo te amo" sound new, and the rhythmic descant on the chorus is a nice touch. The spacy 70s synthesizer which warbles up and down the track is the most interesting thing about the production, once more handled by Colombian mastermind Estéfano. The shuffling gospel rhythm already sounds dated; and while a full choir never comes in, there's enough claustrophobic thickness to the production that it's unnecessary.

Estéfano's lyric is really good, actually, worth looking up and reading through, whether in the original or translation. It's a more or less ordinary love song, but in its details and structure it's the kind of pop-literary performance that deserves a better song, and a better singer.

26.6.17

RICKY MARTIN, “SHE BANGS”

4th November, 2000

Tom Ewing's framing of "imperial phases" in pop is an idea I come back to a lot. It's been fueling how I think about the "Latin invasion" of 1999-2000, in which a brief confluence of popular dance songs, broad ethnic affiliations, and carefully managed careerism made English-language stars out of people who were already (or would be anyway) stars in their own right. The point of imperial phases is that they don't last, and in that sense the Latin Invasion (which Chris Molanphy recently dubbed a "mini-invasion") was unlike the twin British Invasions of the 1960s and 1980s, in that it didn't remake US pop in its image, only flourished for a time and then fell.

The clear end of that imperial phase -- perhaps it would be better to describe it as an imperial moment, a (Re)conquista that was always demographically unsustainable -- would be this song, with its lavish CGI video, its endless remixes for every imaginable market, and its all-in marketing bet on Ricky Martin as a hetero sex symbol, only reaching #12 on the Hot 100. "She Bangs" may be more fondly remembered in the Anglosphere than "Livin' la Vida Loca," perhaps because it's a better song (though not a better production), less fueled by casual misogyny, but it wasn't nearly as big a hit. No need to weep for Ricky Martin, of course: his eventual withdrawal from the English-language pop market was the English-language pop market's loss, not his; as Tom noted in his analysis of imperial phases, it doesn't mean the hits stop. We'll be seeing lots more of Ricky Martin around these parts.

But none of this describes the actual song, a pumping jam with flamenco guitars, salsa -- and later swing -- horns, mambo piano, and... surf guitar again. If it's Livin' la Vida Loca, Mark Two (also produced by Desmond Child), that's not a bad thing to be. Unlike with "Vida Loca," there is an actual Spanish lyric, with the only leftover English phrases "she bangs" and "she moves," appropriately enough, as there are no possible rhythmic equivalents in Spanish. It may not be as misogynist as "Vida Loca," but it's surely as objectifying. Which it's hard to fault Ricky for; nobody ever sounded less lecherous than he does singing this song. Joy this unqualified is almost as rare in pop music as it is elsewhere in life, and just as precious.

Tom Ewing's framing of "imperial phases" in pop is an idea I come back to a lot. It's been fueling how I think about the "Latin invasion" of 1999-2000, in which a brief confluence of popular dance songs, broad ethnic affiliations, and carefully managed careerism made English-language stars out of people who were already (or would be anyway) stars in their own right. The point of imperial phases is that they don't last, and in that sense the Latin Invasion (which Chris Molanphy recently dubbed a "mini-invasion") was unlike the twin British Invasions of the 1960s and 1980s, in that it didn't remake US pop in its image, only flourished for a time and then fell.

The clear end of that imperial phase -- perhaps it would be better to describe it as an imperial moment, a (Re)conquista that was always demographically unsustainable -- would be this song, with its lavish CGI video, its endless remixes for every imaginable market, and its all-in marketing bet on Ricky Martin as a hetero sex symbol, only reaching #12 on the Hot 100. "She Bangs" may be more fondly remembered in the Anglosphere than "Livin' la Vida Loca," perhaps because it's a better song (though not a better production), less fueled by casual misogyny, but it wasn't nearly as big a hit. No need to weep for Ricky Martin, of course: his eventual withdrawal from the English-language pop market was the English-language pop market's loss, not his; as Tom noted in his analysis of imperial phases, it doesn't mean the hits stop. We'll be seeing lots more of Ricky Martin around these parts.

But none of this describes the actual song, a pumping jam with flamenco guitars, salsa -- and later swing -- horns, mambo piano, and... surf guitar again. If it's Livin' la Vida Loca, Mark Two (also produced by Desmond Child), that's not a bad thing to be. Unlike with "Vida Loca," there is an actual Spanish lyric, with the only leftover English phrases "she bangs" and "she moves," appropriately enough, as there are no possible rhythmic equivalents in Spanish. It may not be as misogynist as "Vida Loca," but it's surely as objectifying. Which it's hard to fault Ricky for; nobody ever sounded less lecherous than he does singing this song. Joy this unqualified is almost as rare in pop music as it is elsewhere in life, and just as precious.

12.6.17

CHRISTINA AGUILERA, “VEN CONMIGO (SOLAMENTE TÚ)”

14th October, 2000

Although in low-resolution hindsight it's easy to mistake Christina Aguilera for being part of the wave of young Latinos renovating Latin pop around the turn of the century -- a peer to Jennifer Lopez and Shakira, at least -- this is her sole appearance (as of mid-2017) on this travelogue, and after the comparatively middling sales of Mi Reflejo would rarely record in Spanish again, and then only in duet with an established Latin star.

While she did hire hitmaking Cuban-American songwriter and producer Rudy Pérez (we last saw him assisting Luis Fonsi) to translate "Come on Over Baby (All I Want Is You)" into vernacular Spanish, the production remains pure Stockholm, Johan Åberg's piano, string stabs, and fake scratching ported over wholesale from the English-language original.

So ultimately, despite Aguilera's half-Ecuadorian heritage, "Ven Conmigo" is exactly as much an opportunistic cash-in on the newfound brand-expansion possibilities of the Latin market as any Anglo star might have done: indeed, acts like N'Sync were recording versions of their hits in Spanish, as would Beyoncé years later. That it worked, to the extent that she is one of the exclusive club to have both Hot 100 and Hot Latin #1 hits with the same song, is a tribute to the breezy, galvanic joy of Åberg's production, Pérez' solid work finding rhythmic equivalence in Spanish, and her slightly mechanical but always impressive performance.

It's one of those songs (common early in her career, much rarer later on) when her overdriven vocals sync up with an overdriven emotional state (the excitement of young, sexually curious love), so that her endless elaboration feels like a spontaneous expression of excitement rather than mere showboating. If we're not going to see here again here, at least she left her mark.

Although in low-resolution hindsight it's easy to mistake Christina Aguilera for being part of the wave of young Latinos renovating Latin pop around the turn of the century -- a peer to Jennifer Lopez and Shakira, at least -- this is her sole appearance (as of mid-2017) on this travelogue, and after the comparatively middling sales of Mi Reflejo would rarely record in Spanish again, and then only in duet with an established Latin star.

While she did hire hitmaking Cuban-American songwriter and producer Rudy Pérez (we last saw him assisting Luis Fonsi) to translate "Come on Over Baby (All I Want Is You)" into vernacular Spanish, the production remains pure Stockholm, Johan Åberg's piano, string stabs, and fake scratching ported over wholesale from the English-language original.

So ultimately, despite Aguilera's half-Ecuadorian heritage, "Ven Conmigo" is exactly as much an opportunistic cash-in on the newfound brand-expansion possibilities of the Latin market as any Anglo star might have done: indeed, acts like N'Sync were recording versions of their hits in Spanish, as would Beyoncé years later. That it worked, to the extent that she is one of the exclusive club to have both Hot 100 and Hot Latin #1 hits with the same song, is a tribute to the breezy, galvanic joy of Åberg's production, Pérez' solid work finding rhythmic equivalence in Spanish, and her slightly mechanical but always impressive performance.

It's one of those songs (common early in her career, much rarer later on) when her overdriven vocals sync up with an overdriven emotional state (the excitement of young, sexually curious love), so that her endless elaboration feels like a spontaneous expression of excitement rather than mere showboating. If we're not going to see here again here, at least she left her mark.

7.11.16

THALÍA, “ENTRE EL MAR Y UNA ESTRELLA”

17th June, 2000

To pick up on my analogy from two posts ago, where I said that these Hot Latin #1s are not the tip of the iceberg, but only the tiny portion of the tip exposed to the air (everything below water, in this analogy, never charted at all, but its vast bulk sustains the rest), Thalía's career to this point has taken place entirely within the iceberg, but mostly above the waterline. A pop star in Mexico since 1986, when she joined the juvenile pop group Timbiriche (which also incubated another figure we have yet to meet on this travelogue, but will), and a telenovela star since 1987, she released her first solo album in 1990 and had her first pan-Latin crossover smash in 1994 (with production and songwriting assistance from... Emilio Estefan). That she has not shown up here before is a product of chance, not her lack of starpower.

In fact by 2000 it would be possible for a devoted Latin Pop watcher to think of Thalía as being rather long in the tooth, especially with the sinuous, more forcefully artistic Shakira coming up from behind. (Wait for it...) The success of this song, indeed, bears all the hallmarks of a turn towards adult contemporary: shuffling rhythms and wordless chants lifted from the kind of South African pop that Anglophone stars have been using to sound classy ever since Graceland, twinkly percussion, a vaguely spiritual, nature-infused lyric (the title translates to "between the sea and a star"), and an unflustered performance from Thalía that calls to mind Gloria Estefan at her most comfortable. Since other songs on the album included a Gloria Estefan cover and a remake of the great 60s South African hit "Pata Pata," this feels right at home with other turn-of-the-millennium adult-contemporary hits like Sting's "Desert Rose."

But although "Entre el Mar y una Estrella" was the first single, in the context of the album Arrasando it functions more like a traditional second single, the ballad after the uptempo smash: the electronic "Regresa a Mí" or the punchy title track, which became singles later, would have fit in just fine with the Ricky Martins and Marc Anthonys who were the most exciting things in Latin Pop at the moment. But they didn't hit #1, and this did.

To pick up on my analogy from two posts ago, where I said that these Hot Latin #1s are not the tip of the iceberg, but only the tiny portion of the tip exposed to the air (everything below water, in this analogy, never charted at all, but its vast bulk sustains the rest), Thalía's career to this point has taken place entirely within the iceberg, but mostly above the waterline. A pop star in Mexico since 1986, when she joined the juvenile pop group Timbiriche (which also incubated another figure we have yet to meet on this travelogue, but will), and a telenovela star since 1987, she released her first solo album in 1990 and had her first pan-Latin crossover smash in 1994 (with production and songwriting assistance from... Emilio Estefan). That she has not shown up here before is a product of chance, not her lack of starpower.

In fact by 2000 it would be possible for a devoted Latin Pop watcher to think of Thalía as being rather long in the tooth, especially with the sinuous, more forcefully artistic Shakira coming up from behind. (Wait for it...) The success of this song, indeed, bears all the hallmarks of a turn towards adult contemporary: shuffling rhythms and wordless chants lifted from the kind of South African pop that Anglophone stars have been using to sound classy ever since Graceland, twinkly percussion, a vaguely spiritual, nature-infused lyric (the title translates to "between the sea and a star"), and an unflustered performance from Thalía that calls to mind Gloria Estefan at her most comfortable. Since other songs on the album included a Gloria Estefan cover and a remake of the great 60s South African hit "Pata Pata," this feels right at home with other turn-of-the-millennium adult-contemporary hits like Sting's "Desert Rose."

But although "Entre el Mar y una Estrella" was the first single, in the context of the album Arrasando it functions more like a traditional second single, the ballad after the uptempo smash: the electronic "Regresa a Mí" or the punchy title track, which became singles later, would have fit in just fine with the Ricky Martins and Marc Anthonys who were the most exciting things in Latin Pop at the moment. But they didn't hit #1, and this did.

26.9.16

CARLOS PONCE, “ESCÚCHAME”

4th December, 1999

Three number-one hits in two years: why have I not been including Carlos Ponce along with Iglesias, Martin, Anthony, Fernández, Lopez, and Shakira as the new generation shaking up Latin pop in the late 90s? Well, because he hasn't been anywhere near as good as any of them, for one -- his gruff-voiced power ballads are well below the standard of their sleek pop variety. And for two, this is his last appearance; barring unforeseen comebacks, he will not trouble us again.

So it's something of a pity that his last outing is his best yet. His second album, Todo Lo Que Soy, was produced by Emilio Estefan, for whom it was a banner year: he was involved in nearly all of the 1999 songs I've loved. And "Escúchame" is no power ballad, but an airy folk-pop song, the first pop-flamenco (and not just flamenco-inspired guitar runs) we've heard since Gipsy Kings all the way back in 1990. Ponce is by no means a traditional cantaor, but his husky tones can manage a pop approximation of gitano singing, and he plays off against the handclap rhythms in the last chorus like a pro.

But even though it's a sweet song, and I appreciate the tonal variety of the flamenco sound, it's still not on the level that the new generation is, more like (to reach for contemporary Anglophone comparisons) Everlast's pop-blues-hop than what Britney Spears or Destiny's Child were doing the same year: nice enough, but they're building the future.

Three number-one hits in two years: why have I not been including Carlos Ponce along with Iglesias, Martin, Anthony, Fernández, Lopez, and Shakira as the new generation shaking up Latin pop in the late 90s? Well, because he hasn't been anywhere near as good as any of them, for one -- his gruff-voiced power ballads are well below the standard of their sleek pop variety. And for two, this is his last appearance; barring unforeseen comebacks, he will not trouble us again.

So it's something of a pity that his last outing is his best yet. His second album, Todo Lo Que Soy, was produced by Emilio Estefan, for whom it was a banner year: he was involved in nearly all of the 1999 songs I've loved. And "Escúchame" is no power ballad, but an airy folk-pop song, the first pop-flamenco (and not just flamenco-inspired guitar runs) we've heard since Gipsy Kings all the way back in 1990. Ponce is by no means a traditional cantaor, but his husky tones can manage a pop approximation of gitano singing, and he plays off against the handclap rhythms in the last chorus like a pro.

But even though it's a sweet song, and I appreciate the tonal variety of the flamenco sound, it's still not on the level that the new generation is, more like (to reach for contemporary Anglophone comparisons) Everlast's pop-blues-hop than what Britney Spears or Destiny's Child were doing the same year: nice enough, but they're building the future.

Labels:

1999,

carlos ponce,

flamenco,

pop idol,

puerto rico,

usa

12.9.16

RICKY MARTIN, “BELLA”

4th September, 1999

One of the effects of glancing through all the old entries in this blog while getting ready for this return was becoming very embarrassed about how dismissive I was of the many ballads that have made up the bulk of Hot Latin #1s in the twentieth century. Perhaps I'm growing mushy and sentimental in middle age, perhaps I understand Spanish lyricism better than I used to, or perhaps I'm belatedly getting the critical distance which allows me to hear past flimsy or generic production to the emotion, the performance, the song itself. (Particular apologies to Marco Antonio Solís, probably the most undeserved target of my splenetic boredom over the years.)

All this dawned on me while I was listening to "Bella" again and realized that I'm predisposed to rate it highly not because of Ricky Martin's sensitive performance, or because the soaring melody or elegant lyrics are anything out of the ordinary, but just because the production is modern and full-bodied and full of interesting textural accents. The sitar and tabla atmospherics that open it, the falsetto soars leading into the chorus, the fretless bass murmuring throughout, the gated drums, the swirling strings: this is the second most expensive-sounding song we've heard yet. The first, of course, is "Livin' la Vida Loca."

And it's really only within the shadow of that enormous cross-platform hit that "Bella" makes any sense, both as a chart hit at the time and as a pop memory today. As "She's All I Ever Had," it apparently went as high as #2 on the Hot 100, but I have no memory of it, and listening to it now I'm much less impressed with it in English, where the lyrics (and the rhymes) are more generic and the focus is more on the man singing the song than the woman he's singing about.

Not that it's a deathless love song in either language: Ricky Martin was never particularly convincing as a man tortured by love for a woman even before he left the closet, and his performance here is more remarkable for his burnished soulfulness (the song was co-written by Jon Secada, and you can hear hints of his R&B-derived melodicism, even while the tempo lumbers unfunkily) than for any emotional nakedness. Fair enough; lots of straight men have sung unconvincing love songs too. But there's a reason that "Livin' la Vida Loca" and another song still to come are the ones he's remembered for from the millennial era, rather than this.

Labels:

1999,

ballad,

jon secada,

pop idol,

power ballad,

puerto rico,

raga,

ricky martin,

rock en espanol,

usa

14.4.14

RICKY MARTIN, “LIVIN' LA VIDA LOCA”

24th April, 1999

"Give a little more vibe on the track, please..."

I probably crow too often about new realities, new beginnings, new usherings-in of the present era. Reality is manifold; newness begins over every wave. Yet it feels more accurate than ever to say that the millennium begins here -- at least the millennium seen through the specific lens around which this blog is oriented.

It's not the first Hot Latin #1 to also hit #1 on the Hot 100, not by a wide margin (Los Lobos was twelve years ago), but it does introduce a new sense of intimacy between the two charts. Crossover between them will still be rare, but not quite so rare; even if specific songs aren't familiar to both audiences, a good many artists will be. There was a deal of hype the summer of 1999 about a Latin Invasion (which consisted of about three songs), but apart from Tony Concepción's Irakere-imitating trumpet towards the end, there's little that's particularly Latin about "Livin' la Vida Loca."

Indeed, with its whirlwind velocity, rubbery surf guitar, and energetic horn charts, it actually has more in common with that other cod-tropical vogue of the late 90s, third-wave ska, than with anything specifically Puerto Rican. Which is part of the point, both of Martin's crossover pop and of this whole travelogue: Latin identity is not -- cannot be -- tied to some travel-brochure stereotype of UNESCO World Heritage frozen-in-amber cultural practice. Latin people live in the present tense, and Latin pop is modern pop; whatever and whenever that is.

Desmond Child, the producer of "Vida Loca," made his name with the shiny gloss of Bon Jovi and Aerosmith's late-80s hair metal, and that sense of compressed power gives the track its grab-you-by-the-shirt-front immediacy; an important stage in the loudness wars, it was the first all-ProTools hit, electronic even in its Dick Dale gibber, the punchy horns and skittering drum as influenced by the noisy, jungly end of drum 'n' bass as by Child's rock background.

And the lyrics position it directly in Anglophone rock history, the woman who is living the vida loca one with all the brown sugars and witchy women and maneaters that thirty years of guitar-driven misogyny have chronicled. But Martin's performance has none of the spitefulness of a Jagger; he rather admires her rapaciousness than otherwise, and why not? With this production behind him, he's easily able to keep up with her. (And besides, he's not her target. But that's later history bleeding into earlier.) Once more, it's the beginning of the modern era: hedonism presented not as warning temptation or as knowing deviance, but as the basic premise of pop music. EDM, at least in the popular imagination, starts here too.

"Give a little more vibe on the track, please..."

I probably crow too often about new realities, new beginnings, new usherings-in of the present era. Reality is manifold; newness begins over every wave. Yet it feels more accurate than ever to say that the millennium begins here -- at least the millennium seen through the specific lens around which this blog is oriented.

It's not the first Hot Latin #1 to also hit #1 on the Hot 100, not by a wide margin (Los Lobos was twelve years ago), but it does introduce a new sense of intimacy between the two charts. Crossover between them will still be rare, but not quite so rare; even if specific songs aren't familiar to both audiences, a good many artists will be. There was a deal of hype the summer of 1999 about a Latin Invasion (which consisted of about three songs), but apart from Tony Concepción's Irakere-imitating trumpet towards the end, there's little that's particularly Latin about "Livin' la Vida Loca."

Indeed, with its whirlwind velocity, rubbery surf guitar, and energetic horn charts, it actually has more in common with that other cod-tropical vogue of the late 90s, third-wave ska, than with anything specifically Puerto Rican. Which is part of the point, both of Martin's crossover pop and of this whole travelogue: Latin identity is not -- cannot be -- tied to some travel-brochure stereotype of UNESCO World Heritage frozen-in-amber cultural practice. Latin people live in the present tense, and Latin pop is modern pop; whatever and whenever that is.

Desmond Child, the producer of "Vida Loca," made his name with the shiny gloss of Bon Jovi and Aerosmith's late-80s hair metal, and that sense of compressed power gives the track its grab-you-by-the-shirt-front immediacy; an important stage in the loudness wars, it was the first all-ProTools hit, electronic even in its Dick Dale gibber, the punchy horns and skittering drum as influenced by the noisy, jungly end of drum 'n' bass as by Child's rock background.

And the lyrics position it directly in Anglophone rock history, the woman who is living the vida loca one with all the brown sugars and witchy women and maneaters that thirty years of guitar-driven misogyny have chronicled. But Martin's performance has none of the spitefulness of a Jagger; he rather admires her rapaciousness than otherwise, and why not? With this production behind him, he's easily able to keep up with her. (And besides, he's not her target. But that's later history bleeding into earlier.) Once more, it's the beginning of the modern era: hedonism presented not as warning temptation or as knowing deviance, but as the basic premise of pop music. EDM, at least in the popular imagination, starts here too.

Labels:

1999,

crossover,

dance,

english,

pop,

pop idol,

power pop,

puerto rico,

ricky martin,

rock en espanol,

ska,

usa

17.2.14

MDO, “NO PUEDO OLVIDAR”

27 March, 1999

It took until the end of the second decade of this travelogue, but we have finally encountered the group whose name was synonymous with Latin Pop, at least in the US, for the half-decade leading up to the beginning of it. Menudo (for it is they) hit their peak of popularity before 1986, and since then their passionate fanbase had been too small a portion of the overall Latin-music audience in the US to push them to the top before the late 90s made unabashed teenpop fashionable again.

Then again, this isn't quite the world-famous Puerto Rican boy band Menudo, kept famous today by Anglos who remember the 80s shaking thing their heads about how crazy Latin pop culture is; this is four of the five guys who were in Menudo in 1996, when the rights to the name were sold by Edgardo Díaz, the Puerto Rican svengali who had cooked up the concept back in the 70s, to a Panamanian company. So they called themselves MDO and carried on. There was no difference in the sound or the concept: cute boys singing love songs and dancing, and not doing either very well. "No Puedo Olvidar" (tr. I can't forget) isn't one of the more deathless songs we've encountered; its strongest selling point is the drum loop which suggests that someone involved in the production heard M/A/R/R/S at some point. The voices are pretty but personality-free, the lyrics are the definition of bland, the melody is just sticky enough to hang around but not enough to do anything once it's there.

But hey, it's M(enu)DO at number one! Good for these boys, all of whom joined between 1991 and 1995, long after the group's heyday, and only two of whom were even Puerto Rican (Alexis Grullón is Dominican, and Abel Talamántez is Tejano). It's too bad the teenpop-friendly climate didn't catch them on a better single. But stay tuned.

It took until the end of the second decade of this travelogue, but we have finally encountered the group whose name was synonymous with Latin Pop, at least in the US, for the half-decade leading up to the beginning of it. Menudo (for it is they) hit their peak of popularity before 1986, and since then their passionate fanbase had been too small a portion of the overall Latin-music audience in the US to push them to the top before the late 90s made unabashed teenpop fashionable again.

Then again, this isn't quite the world-famous Puerto Rican boy band Menudo, kept famous today by Anglos who remember the 80s shaking thing their heads about how crazy Latin pop culture is; this is four of the five guys who were in Menudo in 1996, when the rights to the name were sold by Edgardo Díaz, the Puerto Rican svengali who had cooked up the concept back in the 70s, to a Panamanian company. So they called themselves MDO and carried on. There was no difference in the sound or the concept: cute boys singing love songs and dancing, and not doing either very well. "No Puedo Olvidar" (tr. I can't forget) isn't one of the more deathless songs we've encountered; its strongest selling point is the drum loop which suggests that someone involved in the production heard M/A/R/R/S at some point. The voices are pretty but personality-free, the lyrics are the definition of bland, the melody is just sticky enough to hang around but not enough to do anything once it's there.

But hey, it's M(enu)DO at number one! Good for these boys, all of whom joined between 1991 and 1995, long after the group's heyday, and only two of whom were even Puerto Rican (Alexis Grullón is Dominican, and Abel Talamántez is Tejano). It's too bad the teenpop-friendly climate didn't catch them on a better single. But stay tuned.

21.5.13

ENRIQUE IGLESIAS, “NUNCA TE OLVIDARÉ”

6th March, 1999

Growth!

Because Enrique Iglesias still holds the record for the most #1 Latin hits in the US — Luis Miguel would have to stage a decade-long comeback to get anywhere near him — at a certain point, this blog just becomes a means of tracking his career arc. And while this isn't the most interesting song he's sung, it's notable for being his most mature performance to date. The fact that it's the first of his #1s that you could imagine his father singing no doubt has a lot to do with that.

"Nunca Te Olvidaré" (I'll never forget you) was the theme song to a Mexican telenovela of the same name, and it's also the first song Enrique Iglesias brought to number one that he's credited for writing and composing alone. I've touched before on the importance of telenovelas to Latin pop — it's similar to, but not the same as, the effect Hollywood soundtracks had on Anglophone pop in the 90s — but by providing an avenue for creative expression and alternative musical identities outside of the rigorous, micromanaged single-album-single-single release schedule of a major label, novelas throw an element of unpredictability and novelty into the fermenting stew of Latin pop. Not that an Iglesias #1 was anything but predictable in 1999 (and there are more to come), but this relatively old-fashioned, restrained song, the second in a row to employ a real string section, is hard to imagine coming out of the pop-industrial complex that so far had governed his career.

The lyrics are the familiar pledging-eternal-love sort — the opening line is "Three thousand years may pass/You may kiss other lips/But I'll never forget you" — which dovetails perfectly with the novela's plot of star-crossed love across multiple generations. It's so old-fashioned, in fact, that it doesn't have a chorus in the usual rock-oriented sense, only A and B sections with variable lyrics, and of course the repeated refrain of the title phrase. It's been years since we've seen that kind of structure, and my affection for it — as well as my delight that Iglesias isn't making hamfisted rock moves — may be coloring my pleasure in this song. He's still overemoting, making up for his vocal deficiencies with strain, but he's learning to improvise a little, if only emotionally.

Growth!

Because Enrique Iglesias still holds the record for the most #1 Latin hits in the US — Luis Miguel would have to stage a decade-long comeback to get anywhere near him — at a certain point, this blog just becomes a means of tracking his career arc. And while this isn't the most interesting song he's sung, it's notable for being his most mature performance to date. The fact that it's the first of his #1s that you could imagine his father singing no doubt has a lot to do with that.

"Nunca Te Olvidaré" (I'll never forget you) was the theme song to a Mexican telenovela of the same name, and it's also the first song Enrique Iglesias brought to number one that he's credited for writing and composing alone. I've touched before on the importance of telenovelas to Latin pop — it's similar to, but not the same as, the effect Hollywood soundtracks had on Anglophone pop in the 90s — but by providing an avenue for creative expression and alternative musical identities outside of the rigorous, micromanaged single-album-single-single release schedule of a major label, novelas throw an element of unpredictability and novelty into the fermenting stew of Latin pop. Not that an Iglesias #1 was anything but predictable in 1999 (and there are more to come), but this relatively old-fashioned, restrained song, the second in a row to employ a real string section, is hard to imagine coming out of the pop-industrial complex that so far had governed his career.

The lyrics are the familiar pledging-eternal-love sort — the opening line is "Three thousand years may pass/You may kiss other lips/But I'll never forget you" — which dovetails perfectly with the novela's plot of star-crossed love across multiple generations. It's so old-fashioned, in fact, that it doesn't have a chorus in the usual rock-oriented sense, only A and B sections with variable lyrics, and of course the repeated refrain of the title phrase. It's been years since we've seen that kind of structure, and my affection for it — as well as my delight that Iglesias isn't making hamfisted rock moves — may be coloring my pleasure in this song. He's still overemoting, making up for his vocal deficiencies with strain, but he's learning to improvise a little, if only emotionally.

Labels:

1999,

ballad,

enrique iglesias,

pop idol,

romantica,

spain,

telenovela,

usa

13.5.13

SHAKIRA, “TÚ”

20th February, 1999

Lyrically it's a straight-down-the-middle love song (as the title, "You," might hint to those who know pop practice) with a sprinkling of Shakira's signature left-field analogies and metaphors on top. The first line is "te regalo mi cintura" (I give you [the gift of] my waist), which sounds just as odd in Spanish as it does in English, but in a genre in which hearts, hands, eyes and lips are regularly proffered, why not other, equally sensual, body parts? The chorus, however, is all straightforward sentiment, in trusty list format. The object of the song ("túúúúú-júúú") is: her sun, the faith by which she lives, the strength of her voice (typical Shakira hyperbole: surely she'd keep that for herself!), the feet with which she walks, her desire to laugh, the goodbye she doesn't know how to say. She's as strong (if eccentric) a writer as she is a singer (on both counts), and here she produces the rare ballad that repays intellectual attention as much as emotional.

When people complain about Shakira's going blonde and chasing a global (i.e. Anglophone) audience (and there are — still! — some who do), it's because the star she was at this point in her career so precisely satisfied a desire in the Latin audience for a performer who was easily as magnetic, as prodigiously talented, and as wildly creative as any US or UK rock star, but who was entirely theirs. Beck and Radiohead don't record albums in Spanish; Spanish-speakers have to go to them in order to enjoy their fruits. Why shouldn't the world have to come to Shakira, instead of the other way round?

But although ¿Dónde Están Los Ladrones? was certainly in conversation with Beck and Radiohead, her sights were already set higher. When next we hear from her, her peers won't be white male rockers, but the young women — black, white, and Latin — who are, in early 1999, already deeply engaged in the process of transforming the face of pop music in the US. Some of them will make their own appearances on this travelogue; like Shakira, they go to their audience, and are comfortable wearing the clothes of many places.

In accordance with convention, the Hot New Pop Star On the Scene's second number one is a ballad, dreamy and vulnerable where "Ciega, Sordomuda" was lively and whip-smart. The fingerprints of 90s transatlantic rock are all over it, from the smeared guitar lines that could code as either alt-country or neo-psychedelic (shades of Cowboy Junkies) to the string section that chugs from "November Rain" to "To the End." She's long since worked out how to perform ballads in her idiosyncratic vocal style, and if she's less assured than she will later become she'll rarely trust herself to be so naked again without receding behind studio trickery and pop history.

Lyrically it's a straight-down-the-middle love song (as the title, "You," might hint to those who know pop practice) with a sprinkling of Shakira's signature left-field analogies and metaphors on top. The first line is "te regalo mi cintura" (I give you [the gift of] my waist), which sounds just as odd in Spanish as it does in English, but in a genre in which hearts, hands, eyes and lips are regularly proffered, why not other, equally sensual, body parts? The chorus, however, is all straightforward sentiment, in trusty list format. The object of the song ("túúúúú-júúú") is: her sun, the faith by which she lives, the strength of her voice (typical Shakira hyperbole: surely she'd keep that for herself!), the feet with which she walks, her desire to laugh, the goodbye she doesn't know how to say. She's as strong (if eccentric) a writer as she is a singer (on both counts), and here she produces the rare ballad that repays intellectual attention as much as emotional.

When people complain about Shakira's going blonde and chasing a global (i.e. Anglophone) audience (and there are — still! — some who do), it's because the star she was at this point in her career so precisely satisfied a desire in the Latin audience for a performer who was easily as magnetic, as prodigiously talented, and as wildly creative as any US or UK rock star, but who was entirely theirs. Beck and Radiohead don't record albums in Spanish; Spanish-speakers have to go to them in order to enjoy their fruits. Why shouldn't the world have to come to Shakira, instead of the other way round?

But although ¿Dónde Están Los Ladrones? was certainly in conversation with Beck and Radiohead, her sights were already set higher. When next we hear from her, her peers won't be white male rockers, but the young women — black, white, and Latin — who are, in early 1999, already deeply engaged in the process of transforming the face of pop music in the US. Some of them will make their own appearances on this travelogue; like Shakira, they go to their audience, and are comfortable wearing the clothes of many places.

8.4.13

CHAYANNE, "DEJARÍA TODO"

12th December, 1998

It's been six years since Puerto Rican pop star Chayanne has bobbed to the surface on these top-of-the-chart waters; although he's been working steadily in the meantime and been relatively successful at it, this still marks something of a comeback for him. Written by Estéfano, a prolific songwriter and producer from Colombia whose previous success stories had included Jon Secada's debut album and Gloria Estefan's Mi Tierra, "Dejaría Todo" continues Chayanne's success with midtempo ballads. This time, thanks to Marcello Azevedo's nylon-stringed guitar, it has what you might call a stereotypically Latin flavor, a vaguely bolero sway, though not so pronounced that the barreling power-ballad chorus gets tripped up in any kind of polyrhythmic syncopation.

It's a "she's leaving me, my world is ending" song — more or less literally — and if the emotional hyperbole of the lyrics doesn't quite match up with the bland, adult-contemporary longeurs of the production, that's nothing new. Chayanne's voice isn't powerful, but it's pretty and well-suited to the aching romanticisms he's called upon to emote. (Enrique Iglesias, for example, would make an unlistenable fist of what Chayanne relaxes into.) It goes on for too long, as the chorus repeats and repeats, but it remains listenable throughout, Estéfano's production magic keeping each instrumental injection just this side of stultifying. The choral effect on the last several iterations of the chorus is both gilding this particular lily and getting to be a bit tiresome on this travelogue — how many faux-gospel choruses does that make within the past year? — but I'm surprised to discover that I have some affection for Chayanne.

Which is good, because he'll be back.

It's been six years since Puerto Rican pop star Chayanne has bobbed to the surface on these top-of-the-chart waters; although he's been working steadily in the meantime and been relatively successful at it, this still marks something of a comeback for him. Written by Estéfano, a prolific songwriter and producer from Colombia whose previous success stories had included Jon Secada's debut album and Gloria Estefan's Mi Tierra, "Dejaría Todo" continues Chayanne's success with midtempo ballads. This time, thanks to Marcello Azevedo's nylon-stringed guitar, it has what you might call a stereotypically Latin flavor, a vaguely bolero sway, though not so pronounced that the barreling power-ballad chorus gets tripped up in any kind of polyrhythmic syncopation.

It's a "she's leaving me, my world is ending" song — more or less literally — and if the emotional hyperbole of the lyrics doesn't quite match up with the bland, adult-contemporary longeurs of the production, that's nothing new. Chayanne's voice isn't powerful, but it's pretty and well-suited to the aching romanticisms he's called upon to emote. (Enrique Iglesias, for example, would make an unlistenable fist of what Chayanne relaxes into.) It goes on for too long, as the chorus repeats and repeats, but it remains listenable throughout, Estéfano's production magic keeping each instrumental injection just this side of stultifying. The choral effect on the last several iterations of the chorus is both gilding this particular lily and getting to be a bit tiresome on this travelogue — how many faux-gospel choruses does that make within the past year? — but I'm surprised to discover that I have some affection for Chayanne.

Which is good, because he'll be back.

Labels:

1998,

bolero,

chayanne,

estefano,

pop idol,

power ballad,

puerto rico,

romantica

25.3.13

SHAKIRA, “CIEGA, SORDOMUDA”

21st November, 1998

And the last piece of millennial-era Latin Pop falls into place. Here we enter the modern world.

Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll had been a child prodigy, writing songs at eight years old and releasing her first album at thirteen; but it wasn't until her third album, Pies Descalzos, that she came into her own: a combination of rock energy, dance rhythms, and pan-global sonics unified by her unmistakable, sweet-and-sour voice and a real brilliance in lyric writing that pushed past conventional expressions of love or self to incorporate bizarre imagery, extravagant hyperbole and unusually rhythmic uses of language. The gospel-tinged "Estoy Aquí", her first mature hit, and the first to do business outside of Colombia, turns the chorus into a breathless rush of syllables imitating the intense everything-at-once emotional whirlwind of the adolescence she was still emerging from.

But that was three years ago, in 1995. And because this travelogue only skims along the surface of the Latin Chart, we have been unable to track her progress. Very few (non-Iglesias) performers begin their careers at the top of any chart; the slow and patient building of a coalition of fanbases, of proving that you make solid work and that listeners can trust you with their ears, hips, and heart, of inculcating enough of an image that it's a surprise and a scandal when you subvert or expand it, is a longer, more arduous, and perhaps more honest task. Shakira in the 90s was not unlike Madonna in the 80s: a bolt of lightning, as ambitious as she was talented, and hard-working enough to compensate for any deficiencies either way. Although I'd say that Shakira was more purely talented than Madonna ever was as a singer, songwriter, and dancer, and on more or less the same level as an applied theorist of popular music; "Estoy Aquí," in that comparison, would be her early, "Holiday"-era light dance material. "Ojos Así" would be her imperial-era, "Like A Prayer"/"Express Yourself" material. And "Ciega, Sordomuda" would be, oh, say "Into the Groove."

Comparisons can only carry you so far, however: real understanding requires the thing itself. And "Ciega, Sordomuda" is very much a product of the late 90s: the light house beat touches on Swedish pop of the era (the Cardigans, Yaki-Da, Robyn), the mariachi trumpet and guitar were accenting everything from No Doubt to Cake, and even her voice could be similar enough to Alanis Morissette's pained yowl that comparisons litter many of the early English-language introductions to the new Colombian pop/rock starlet. But the sonics of the song, however pleasurable, are only part of what makes it so masterful a piece of pop music: the lyrics, the structure, and Shakira's performance do the rest.

"Ciega, Sordomuda" means "blind, deaf and mute," and are part of an extensive catalog of adjectives she applies to herself as the result of her lover's proximity. (The full list: bruta, ciega, sordomuda, torpe, traste, y testaruda; ojerosa, flaca, fea, desgreñada, torpe, tonta, lenta, nécia, desquiciada, completamente descontrolada. Or: crude, blind, deaf, mute, awkward, clumsy and mulish; haggard, skinny, ugly, unkempt, awkward, foolish, slow, stupid, unhinged, completely out of control ― all of them, naturally, cast in the feminine.) This kind of self-abasement would be unthinkable in English-language pop, especially from such an extremely attractive and self-possessed woman, but it's undoubtedly a faithful report of the kinds of things many of us have felt in the presence of someone who pushes our buttons.

Even her ability with hooks serves the emotional content of the song: apart from the chanting chorus, the swooning "ai, yai yai, yai yai"s that follow the chorus and make space for emotion entirely separate from words are beautiful, sentimental, silly, and sad. Then there's the middle eight, with angry guitars and the bulk of the adjective assault, in which she spits "y no me eschuchas lo que te digo" (and you don't listen to what I'm telling you), admitting that not only is it an incapacitating love, but a hopeless one as well. Shakira's privileging of the contrary and grandly silly vacillations of the human heart over being cool or even making sense has been one of her greatest and most consistent features as a writer over the years.

We'll have plenty of further opportunities to see this in practice: now that she's finally here, Shakira will be a frequent return visitor to the top spot, and indeed the next decade-plus in Latin Pop might well be considered the Shakira Era. Although the chart is getting too busy and diverse for it to be dominated by any one voice, if any voice deserved to dominate, it would be hers.

And the last piece of millennial-era Latin Pop falls into place. Here we enter the modern world.

Shakira Isabel Mebarak Ripoll had been a child prodigy, writing songs at eight years old and releasing her first album at thirteen; but it wasn't until her third album, Pies Descalzos, that she came into her own: a combination of rock energy, dance rhythms, and pan-global sonics unified by her unmistakable, sweet-and-sour voice and a real brilliance in lyric writing that pushed past conventional expressions of love or self to incorporate bizarre imagery, extravagant hyperbole and unusually rhythmic uses of language. The gospel-tinged "Estoy Aquí", her first mature hit, and the first to do business outside of Colombia, turns the chorus into a breathless rush of syllables imitating the intense everything-at-once emotional whirlwind of the adolescence she was still emerging from.

But that was three years ago, in 1995. And because this travelogue only skims along the surface of the Latin Chart, we have been unable to track her progress. Very few (non-Iglesias) performers begin their careers at the top of any chart; the slow and patient building of a coalition of fanbases, of proving that you make solid work and that listeners can trust you with their ears, hips, and heart, of inculcating enough of an image that it's a surprise and a scandal when you subvert or expand it, is a longer, more arduous, and perhaps more honest task. Shakira in the 90s was not unlike Madonna in the 80s: a bolt of lightning, as ambitious as she was talented, and hard-working enough to compensate for any deficiencies either way. Although I'd say that Shakira was more purely talented than Madonna ever was as a singer, songwriter, and dancer, and on more or less the same level as an applied theorist of popular music; "Estoy Aquí," in that comparison, would be her early, "Holiday"-era light dance material. "Ojos Así" would be her imperial-era, "Like A Prayer"/"Express Yourself" material. And "Ciega, Sordomuda" would be, oh, say "Into the Groove."

Comparisons can only carry you so far, however: real understanding requires the thing itself. And "Ciega, Sordomuda" is very much a product of the late 90s: the light house beat touches on Swedish pop of the era (the Cardigans, Yaki-Da, Robyn), the mariachi trumpet and guitar were accenting everything from No Doubt to Cake, and even her voice could be similar enough to Alanis Morissette's pained yowl that comparisons litter many of the early English-language introductions to the new Colombian pop/rock starlet. But the sonics of the song, however pleasurable, are only part of what makes it so masterful a piece of pop music: the lyrics, the structure, and Shakira's performance do the rest.

"Ciega, Sordomuda" means "blind, deaf and mute," and are part of an extensive catalog of adjectives she applies to herself as the result of her lover's proximity. (The full list: bruta, ciega, sordomuda, torpe, traste, y testaruda; ojerosa, flaca, fea, desgreñada, torpe, tonta, lenta, nécia, desquiciada, completamente descontrolada. Or: crude, blind, deaf, mute, awkward, clumsy and mulish; haggard, skinny, ugly, unkempt, awkward, foolish, slow, stupid, unhinged, completely out of control ― all of them, naturally, cast in the feminine.) This kind of self-abasement would be unthinkable in English-language pop, especially from such an extremely attractive and self-possessed woman, but it's undoubtedly a faithful report of the kinds of things many of us have felt in the presence of someone who pushes our buttons.

Even her ability with hooks serves the emotional content of the song: apart from the chanting chorus, the swooning "ai, yai yai, yai yai"s that follow the chorus and make space for emotion entirely separate from words are beautiful, sentimental, silly, and sad. Then there's the middle eight, with angry guitars and the bulk of the adjective assault, in which she spits "y no me eschuchas lo que te digo" (and you don't listen to what I'm telling you), admitting that not only is it an incapacitating love, but a hopeless one as well. Shakira's privileging of the contrary and grandly silly vacillations of the human heart over being cool or even making sense has been one of her greatest and most consistent features as a writer over the years.

We'll have plenty of further opportunities to see this in practice: now that she's finally here, Shakira will be a frequent return visitor to the top spot, and indeed the next decade-plus in Latin Pop might well be considered the Shakira Era. Although the chart is getting too busy and diverse for it to be dominated by any one voice, if any voice deserved to dominate, it would be hers.

7.1.13

CARLOS PONCE, “DECIR ADIÓS”

26th September, 1998

The first time Carlos Ponce came up, I noted that he had gotten his start in telenovelas; and it's worth noting that a few months after this, he'd be guest starring on both Beverly Hills 90210 and 7th Heaven as generic Latin pretty boys. "Decir Adiós" doesn't do much to dispel the pretty-boy air; although it has more gravitas than "Rezo," it's if anything even less demanding of his limited vocal capabilities. He gets to growl sandily, and murmur throatily, and the rest of the track's emotion is up to the backing orchestra-plus-wailing-guitar.

The song itself is practically the definition of "generic rock ballad" -- the title translates to "Say Goodbye," a title that has covered hundreds of songs over the years -- and what interest it manages to scrape up is due largely to the dramatic, pause-and-crescendo arrangement led by electric piano, an arrangement which Ponce barrels through with little grace, relying on the inherent sexiness of his voice to carry him through in much the same way as he relied on the inherent sexiness of his look to carry him through acting. I'm afraid I'm immune to those particular charms; I'm left wondering, again, what a really strong singer, a Ricky Martin or a Marc Anthony, might have made of the song.

The first time Carlos Ponce came up, I noted that he had gotten his start in telenovelas; and it's worth noting that a few months after this, he'd be guest starring on both Beverly Hills 90210 and 7th Heaven as generic Latin pretty boys. "Decir Adiós" doesn't do much to dispel the pretty-boy air; although it has more gravitas than "Rezo," it's if anything even less demanding of his limited vocal capabilities. He gets to growl sandily, and murmur throatily, and the rest of the track's emotion is up to the backing orchestra-plus-wailing-guitar.

The song itself is practically the definition of "generic rock ballad" -- the title translates to "Say Goodbye," a title that has covered hundreds of songs over the years -- and what interest it manages to scrape up is due largely to the dramatic, pause-and-crescendo arrangement led by electric piano, an arrangement which Ponce barrels through with little grace, relying on the inherent sexiness of his voice to carry him through in much the same way as he relied on the inherent sexiness of his look to carry him through acting. I'm afraid I'm immune to those particular charms; I'm left wondering, again, what a really strong singer, a Ricky Martin or a Marc Anthony, might have made of the song.

Labels:

1998,

ballad,

carlos ponce,

pop idol,

power ballad,

puerto rico,

romantica

12.8.12

CARLOS PONCE, “REZO”

27th June, 1998

Carlos Ponce was an actor, pinup, and singer, in that order; he'd been working in telenovelas since 1990, when he was eighteen, and the fact that it took until 1998 for him to release a debut album suggests that music was neither his first passion nor the most efficient use of his talents.

Carlos Ponce was an actor, pinup, and singer, in that order; he'd been working in telenovelas since 1990, when he was eighteen, and the fact that it took until 1998 for him to release a debut album suggests that music was neither his first passion nor the most efficient use of his talents.

Or maybe I'm just letting the performance influence my reckoning. There's nothing about it which suggests a distinct musical personality: the dreamy-ballad-into-gospel-swayalong format is cribbed from Ricky Martin, the gruff, limited-range singing (until he finally lets off a single falsetto peal in the outro) is reminiscent of nonsinging actors forced to sing anyway from Richard Harris to Johnny Depp, and the indistinctly anonymous instrumentation that puts him front and center makes it clear that it's not music but showbiz that is really being celebrated here. The gospel choir makes up for his own improvisatory deficiencies and lack of mellifluousness; it's almost as if that was the idea.

The song itself is a glib declaration of love: "Rezo" means "I pray," though the connotation leans more towards the recitation of Catholic prayer than to the impulsive spirit of evangelical prayer. Which may be one way of explaining the poor match between song and style; the entirely secular subject of his prayer is that she love him back, "y que mi vida decores con tus gustos, tus colores" (and decorate my life with your tastes, your colors). It's the kind of thing that would be sweet if sung in a romantic comedy and creepily terrifying in real life. Which is true of most pop, probably; but Ponce's not a strong enough musical actor to sell the idea convincingly.

Labels:

1998,

ballad,

carlos ponce,

gospel,

pop idol,

puerto rico

6.8.12

SERVANDO Y FLORENTINO, “UNA FAN ENAMORADA”

9th May, 1998

1998 was, globally speaking, the year of the boyband. In the wake of the dissolution of British stalwarts Take That, a new generation of groups like the Backstreet Boys, *NSYNC, Boyzone, Steps, 98º, and Westlife rushed in to fill the void. The pull of this rising global tide was felt in Latin pop as well — former boyband icon Ricky Martin established himself as a solo artist (not unlike Robbie Williams in the UK), and Servando y Florentino scored, Hanson-like, a solitary left-field #1 out of the Venezuelan pop-salsa scene.

Seventeen and sixteen respectively the week this song hit #1, Servando and Florentino Primera had been homeland heroes for several years already as the voices of La Orquesta Salserín, one of the primary competitors to Menudo throughout the Americas. Like Enrique Iglesias, they had a respectable pop lineage: their father, Alí Primera, had been one of the shining lights of Venezuelan nueva canción in the 60s and 70s; and like Marc Anthony, they stood by the relative authenticity of salsa despite their unabashedly pop profile.

Not that Marc Anthony had anything to worry about. "Una Fan Enamorada" ("a [female] fan in love") is very much boyband material, from the plushy pop-disco melody (recalling an earlier era of boyband, the Bee Gees) to the lyrics' apparently-sympathetic-but-on-examination-not-really portrait of their own fanbase. Such songs are always exercises in ego-stroking for the singers — even when they approach the tragic near-perfection of Eminem's "Stan," the unspoken premise is still how great the artist must be to inspire such cracked devotion in the first place. "Ours, my boy, is a high and lonely destiny."

And Servando and Florentino aren't quite up to even the relatively gentle rigors of the song. The highest reaches of the melody scrape against the limitations of their immature voices, and even the closest thing salsa has to a sure thing, the funky breakdown at the end, is rendered glib and pointless by their inability to riff convincingly. Like too many boybands, they were the sound of a season, and struggle to be heard to any great effect beyond.

1998 was, globally speaking, the year of the boyband. In the wake of the dissolution of British stalwarts Take That, a new generation of groups like the Backstreet Boys, *NSYNC, Boyzone, Steps, 98º, and Westlife rushed in to fill the void. The pull of this rising global tide was felt in Latin pop as well — former boyband icon Ricky Martin established himself as a solo artist (not unlike Robbie Williams in the UK), and Servando y Florentino scored, Hanson-like, a solitary left-field #1 out of the Venezuelan pop-salsa scene.

Seventeen and sixteen respectively the week this song hit #1, Servando and Florentino Primera had been homeland heroes for several years already as the voices of La Orquesta Salserín, one of the primary competitors to Menudo throughout the Americas. Like Enrique Iglesias, they had a respectable pop lineage: their father, Alí Primera, had been one of the shining lights of Venezuelan nueva canción in the 60s and 70s; and like Marc Anthony, they stood by the relative authenticity of salsa despite their unabashedly pop profile.

Not that Marc Anthony had anything to worry about. "Una Fan Enamorada" ("a [female] fan in love") is very much boyband material, from the plushy pop-disco melody (recalling an earlier era of boyband, the Bee Gees) to the lyrics' apparently-sympathetic-but-on-examination-not-really portrait of their own fanbase. Such songs are always exercises in ego-stroking for the singers — even when they approach the tragic near-perfection of Eminem's "Stan," the unspoken premise is still how great the artist must be to inspire such cracked devotion in the first place. "Ours, my boy, is a high and lonely destiny."

And Servando and Florentino aren't quite up to even the relatively gentle rigors of the song. The highest reaches of the melody scrape against the limitations of their immature voices, and even the closest thing salsa has to a sure thing, the funky breakdown at the end, is rendered glib and pointless by their inability to riff convincingly. Like too many boybands, they were the sound of a season, and struggle to be heard to any great effect beyond.

18.6.12

RICKY MARTIN, “VUELVE”

28th February, 1998

And now, as if we were only waiting for Céline to put the capstone on the era, we are fully immersed in modern Latin Pop. Ricky Martin has been a professional singer and entertainer for more than a decade at this point, from his early days in the revolving-door Puerto Rican boy band Menudo to his increasing profile not just in Latin music but crossover dance as well, and he sounds like it, relaxed and professional, with a lively soul/rock delivery — everything Enrique Iglesias wants to be but isn't, not yet.

In fact we haven't heard anything this confident, or this indebted to Stateside R&B, in a long time; not since Selena, or even Jon Secada. Although this is R&B as filtered through Anglo-American pop/rock aesthetics, a loose soul vamp that sweeps up into a declamatory chorus, with broad key changes and plenty of room for a singer to show off, if that's the sort of thing he's inclined to do. Martin's not, for the most part, but that doesn't mean he hasn't got the tools to do it with.

The comparison that keeps urging itself to me is to George Michael, and while I don't want to make too much of it (gay dance-rock-soul men with brilliant smiles who came out later in their careers, after their hitmaking days were behind them), the ease and mastery with which Martin nagivates the funk-flecked power ballad form, swooping up into falsetto on the chorus and engaging gleefully with the gospel choir in the final third, is very Michaelian.

"Vuelve" ("return," both the noun and the imperative) was also the title of its parent album, Martin's fourth, on which he finally scaled the heights of the Latin chart. It was written by the Venezuelan Franco De Vita, who we last saw making a not-so-convincing effort at Anglo-American gospelly rock dynamics. Martin's boyband-bred sense of rhythm is one key improvement, but the big one is that "Vuelve" is not nearly so self-important a song as "No Basta" — while certainly pulling out a big gospel choir for the final chorus is a time-honored Seriousness Indicator, it's impossible to take the grinning sway of Martin's performance as seriously as the lyrics would like us to. Sure, he's begging for his lover's return — without him*, life has no meaning, even air has deserted his lungs — but Martin never sounds anything but totally confident that he* will return.

*I know it's not really kosher to make assumptions about the gender of non-gendered objects of song, especially since Martin was very much still in the closet in 1998, but I'm enough of an English traditionalist that I revolt at the prospect of "hir" or "s/he," and entirely feminine pronouns are equally problematic.

And now, as if we were only waiting for Céline to put the capstone on the era, we are fully immersed in modern Latin Pop. Ricky Martin has been a professional singer and entertainer for more than a decade at this point, from his early days in the revolving-door Puerto Rican boy band Menudo to his increasing profile not just in Latin music but crossover dance as well, and he sounds like it, relaxed and professional, with a lively soul/rock delivery — everything Enrique Iglesias wants to be but isn't, not yet.

In fact we haven't heard anything this confident, or this indebted to Stateside R&B, in a long time; not since Selena, or even Jon Secada. Although this is R&B as filtered through Anglo-American pop/rock aesthetics, a loose soul vamp that sweeps up into a declamatory chorus, with broad key changes and plenty of room for a singer to show off, if that's the sort of thing he's inclined to do. Martin's not, for the most part, but that doesn't mean he hasn't got the tools to do it with.

The comparison that keeps urging itself to me is to George Michael, and while I don't want to make too much of it (gay dance-rock-soul men with brilliant smiles who came out later in their careers, after their hitmaking days were behind them), the ease and mastery with which Martin nagivates the funk-flecked power ballad form, swooping up into falsetto on the chorus and engaging gleefully with the gospel choir in the final third, is very Michaelian.

"Vuelve" ("return," both the noun and the imperative) was also the title of its parent album, Martin's fourth, on which he finally scaled the heights of the Latin chart. It was written by the Venezuelan Franco De Vita, who we last saw making a not-so-convincing effort at Anglo-American gospelly rock dynamics. Martin's boyband-bred sense of rhythm is one key improvement, but the big one is that "Vuelve" is not nearly so self-important a song as "No Basta" — while certainly pulling out a big gospel choir for the final chorus is a time-honored Seriousness Indicator, it's impossible to take the grinning sway of Martin's performance as seriously as the lyrics would like us to. Sure, he's begging for his lover's return — without him*, life has no meaning, even air has deserted his lungs — but Martin never sounds anything but totally confident that he* will return.

*I know it's not really kosher to make assumptions about the gender of non-gendered objects of song, especially since Martin was very much still in the closet in 1998, but I'm enough of an English traditionalist that I revolt at the prospect of "hir" or "s/he," and entirely feminine pronouns are equally problematic.

Labels:

1998,

gospel,

pop idol,

power ballad,

puerto rico,

ricky martin,

rock en espanol

29.5.12

ALEJANDRO FERNÁNDEZ, “SI TÚ SUPIERAS”

18th October, 1997

As if to prove that Enrique Iglesias isn't the only son of a famous Latin singer of the 70s and 80s who can command attention, respect, and screaming devotion, here's another extremely recognizable last name. Although we did, if briefly, meet Julio Iglesias early on in this chart voyage, we never directly encountered Vicente Fernández. This is more or less an effect of when the chart began; if it had been running in the 70s and early 80s, he would have waged serious siege to Iglesias' domination. Fernández pére was (and still is) the greatest ranchera singer of his generation and arguably of all time, comparable perhaps to George Jones' position in country music, and if his music didn't always have the transnational appeal of Julio Iglesias pére's, the devotion of his Mexican and Mexican-American fanbase was, and remains, a force to be reckoned with.

Fernández fils began his career following in his father's footsteps, with ranchera and mariachi albums in the early 90s, and had moderate-to-high levels of success. But in 1997 -- and I can't imagine he didn't have one shrewd eye on the stunning success of baby-faced Iglesias fils -- he joined up with Emilio Estefan and Kike Santander, the twin forces behind the throne de la Gloria, and recorded an album of modern bolero, not unlike what Luis Miguel has been doing, but more dynamically arranged. If he was attempting to challenge Enrique for top-of-the-chart supremacy, it worked: "Si Tú Supieras" ("if you knew") was the biggest Latin hit of the second half of 1997, with Fernández' strongest advantage over Iglesias -- his polished, resonant voice -- front and center.