15th September, 2012

One of the few upsides of having taken forever to get through this blog is that songs that had yet to be released when I began it are able to force me to revisit and revise some of the ill-informed, unconsidered, and shallow takes I gave in the first few years of its existence.

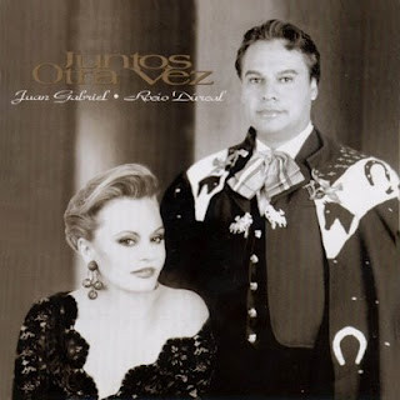

Juan Gabriel, first as a songwriter and then a week later as a singer, was the auteur who more than any other defined the first five years of Hot Latin #1s, and I never really appreciated what made him great when I was writing about those years. It was not until his final #1 as a singer in 2001 -- which I only got to after his death in 2016, when I was finally capable of understanding the full breadth of his achievement -- that I really gave him his due in these pages.

But it wasn't in these pages, but in the waning years of the music-writing community on Tumblr, that I really revised my understanding of Juan Gabriel: my somewhat bellicose and overheated in memoriam included twinned valuations of "Debo Hacerlo," a #1 which I had done less than justice to back in 2010, and its immediate predecessor, the epic-length power ballad "Hasta Que Te Conocí," which peaked at #2 and so which I had been ignorant of until his death, when I dove into his discography and learned, to my mortification, that "Debo Hacerlo" had always been a kind of Frankensteined remix of "Conocí," the kind of obvious context that any Spanish-language listener in the eighties would have known immediately and which this blog would theoretically exist to elucidate for English-only readers. I've mentioned before how embarrassed I am by the first two decades covered by this blog, but that entry might be the one of which I'm most ashamed.

I'll go ahead and reproduce my post-mortem Tumblr blurb for "Hasta Que Te Conocí" here, in order to give a starting point for considering Maná's 2012 cover:

In 1986, he had no worlds left to conquer. (The savage wilderness to the north had never counted; it would have been beneath his dignity to mouth their crude, unliterary tongue.) The supreme center of Mexican music, he moved with ease between the internationalist pop of the capital, the classicist ranchera of the provinces, and the party-hearty rock of the border. His songs were sung by Spanish divas and juvenile sensations, he was the face and voice of the television age. With no horizontal territory left to claim, he could only build up: to pierce the sky with monuments to his own emotional torment and eccentric but undeniable musicianship.

“Hasta Que Te Conocí” is an sprawling pop edifice built from ranchera materials, but on a plan only Juan Gabriel could have conceived. An extended ambient ballad built on folkloric repetition and declarations of prelapsarian innocence serves as introduction, his perfectly-timed phrasing the only element of rhythm. When he finally pivots to the title phrase, tight mariachi strums and doomy horns build tension as he lays out his accusation of heartbreak and betrayal. It winds tighter and tighter, until the whole arrangement rises into an extended march-cum-tango-cum-montuno, horns pealing dolorously as Gabriel’s voice raises at last in emotional refusal, the tightly-constructed argument thrown out the window for a repeated, sobbing “no te quiero verte más.” The original studio version is stunning enough, but for the full, extravagantly emotional, experience see his epochal 1990 concert version or even his rendition from earlier this year, arranged and conducted by his longtime champion, composer Eduardo Magallanes.

(I will leave my reevaluation of "Debo Hacerlo" for the clickthrough; I may even have more to say later this year thanks to assorted music nerd challenges on Bluesky.)

Despite my insistence that only Juan Gabriel could have conceived of or pulled off the weird, ungainly, intensely personal structure of "Hasta Que Te Conocí" (tr. "Until I met you"), it's been a frequent target for cover versions in the years since 1986, much in the way that similarly extravagant slabs of high camp in the Anglophone canon like "Bohemian Rhapsody" or "Total Eclipse of the Heart" have been. Merengue, rock, and hip-hop versions all reached the lower reaches of the Hot Latin chart between 1987 and 2009, but the most successful covers would by Marc Anthony's faithful 1991 salsa cover (which reached #13) and, of course, this 2012 rendition by veteran rockers Maná.

I've been very hard on Maná in these pages, especially their latter-day resurgence as a mainstay of the #1 spot -- and it's a little comical that I implied they were in some way antithetical to Juan Gabriel in their first appearance here, given the fact that this cover was waiting for me -- but I have to admit that this is a sensitive, well-delivered cover, primarily in gentle bolero time until they go all Santana on a montuno coda, with Fher keeping his dudely rock bellowing to a minimum. But I can only come to that conclusion after spending weeks away from Juan Gabriel's original: when I listen to them back to back, Maná's limited emotional landscape and unimaginative rock instrumentation stand out in stark relief.

I have no memory of hearing this on the radio at the time, but like so many entries this year, it was only at #1 for a week: the last grains of sand of the airplay-only Hot Latin chart are running out fast.