7th August, 1993

Unlikely as it sounds, this is only Gloria Estefan's second appearance in these chronicles. She was far and away the most popular Latin act in the Anglophone market, having racked up a string of hits comparable to Madonna's or Janet Jackson's, at least for consistency if not longevity. I was barely paying attention at the time, and even I remember "Mi Tierra" as a sort of back-to-her-roots move after the campy strut of "Go Away."

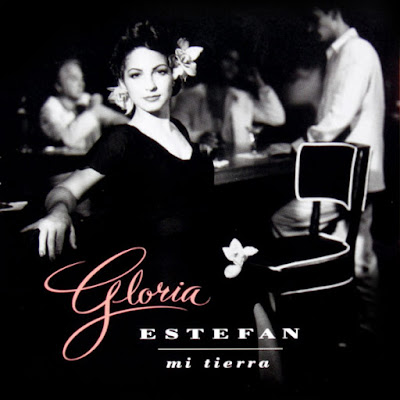

But the Latin market was more astringent, demanding songs in Spanish, and Mi Tierra, at long last, complied. Her first all-Spanish-language album, it was less sleek and modern than much of the music she had been making, with or without the Sound Machine. Not that she had ever been particularly cutting-edge or critically acclaimed, rock purists recoiling from her dance-pop diva roots and diva fans skeptical of her sometimes corny sense of humor and often-weak material. Mi Tierra was that particularly rockist move, the back-to-roots record, and let her diva tear into some meaty emotions with mature sensibilities and precise control, and she was rewarded for it in Grammies, sales, and the loving embrace of Latin Pop radio. For the rest of the 90s, Gloria Estefan will be a much more recurrent figure here — just as she begins to fade from sight in English-language pop.

The first single off the album, "Mi Tierra" ("my land") is practically a textbook in Cuban dance styles, beginning with a folk-African drumbeat and shimmying into a guajira, a son, a rumba, and finally, when the horns come in, puro salsa. The lyrics are perhaps the best set of lyrics we've seen to date on this journey, an impressionistic, fragmented, and emotionally charged immigrant's monologue. Estefan herself was born in Cuba but her family escaped to the US when Castro took power; she has not returned. The song is as much an exile's song as an immigrant's, full of longing for the beloved homeland and musical reverie, but as she works her way up to the climax of the song (just before the horns come in), she grows more and more passionate: "sufro eso dolor que hay en su alma, aunque estoy lejos yo lo siento, y ¿un día regreso?" ("I suffer that pain born in [my country's] heart, though I am far away I feel it, and will I return one day?") The question hangs in the air for the briefest of seconds, before the answer is pounded out in three sharp hits: "Yo no sé." ("I don't know.")

Even the music dies away with the anguish of the unresolved, impossible-to-resolve question, before rushing back in harder and fiercer than ever, the horns blare in reckless joy, and even soothing disco strings flutter in. But the flutes still shriek unquietly, and the drums as frantic as ever: the call-and-response returns, as she cries out that she will remember, she will bear witness, her blood runs hot, she carries her tierra within her, and the voices ring back in response "mi tierra ... mi tierra ... mi tierra" in nasal unison after the fashion of traditional Latin American backing singers. The music rises again, the horns implacable, the disquiet overwhelming, and ends on the highest pitch of emotion possible, leaving the listener exhilarated but (if they have understood the words) emotionally drained.

It's a hell of a song, and I hear more in it every time I return to it. It was even a minor hit on various English-language charts, including in the UK and Australia; and I have to wonder why it's not talked about more. Is the Spanish language too daunting? The Cubanismo too specific? Estefan herself too easily dismissed as a pop lightweight? (I've done it myself, based mostly on the fact that everyone I knew who liked her in the 90s were women in their forties.) Consider this a call for Gloria Estefan Reappraisal Month. Or at the very least, point me to the places I've missed where people have given her her due.